No, the Mexico City Policy does not drive up international abortion rates.

One of the first actions the new Biden Administration is expected to take (which has yet to happen as of this writing) is the repeal of the Mexico City Policy. The policy originated under Ronald Reagan and prevents US foreign aid funds for family planning from going to organizations that perform abortions or advocate for their legalization in developing nations, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa.

This policy has fluctuated since its foundation, as it has been reversed under all Democratic presidents since Clinton and then re-enacted under all Republicans since Reagan.

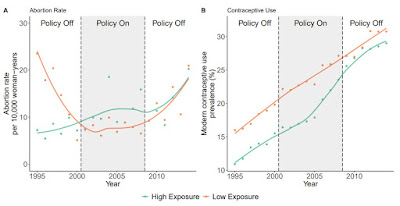

Pro-choice critics of the policy, labeling it the “global gag rule,” argue that restricting funds from family planning organizations in Africa harms women by making access to contraception and clinical abortions difficult or impossible. In fact, these critics point to a few studies that seem to confirm this (one in 2011, one in 2018, and the latest in 2019). The 2019 study, published in Lancet Global Health by Brooks et al., is more comprehensive than the previous studies and analyzes data from three administrations (Clinton, W. Bush, and Obama). They analyze data on abortion and modern contraceptive use in 26 African countries and label some “high exposure” (hereafter HE) if they are most dependent on US foreign aid, and therefore more affected by the Mexico City policy, and others “low exposure” (hereafter LE) if they are least affected. The authors explain:

Our paper finds a substantial increase in abortions across sub-Saharan Africa among women affected by the US Mexico City Policy. This increase is mirrored by a corresponding decline in the use of modern contraception and increase in pregnancies under the policy. This pattern of more frequent abortions and lower contraceptive use was also reversed after the policy was rescinded.

Based on this summary, one might conclude that Brooks et al found that when the Mexico City policy is in place, abortions rise and contraception use decreases, and once the policy is reversed, abortions decrease and contraception use increases, especially in HE countries. And yet this relationship is not what the study found. As the authors explain in the supplemental material (Figure S4):

|

| (Click to enlarge) |

There is no clear pattern here of contraception use decreasing and/or abortion rates increasing during the policy. In fact, the pattern of increasing contraceptive use in both HE and LE countries is consistent regardless of whether or not the Mexico City policy is in place. HE countries had lower contraceptive use from the beginning, but use increased more sharply around 2005, during the Bush administration, and continued to increase under Obama at a steadier pace.

The abortion rate chart is much more scattered, possibly reflecting unreliable reporting (more on that below), but taken at face value, the trends seem mostly independent of the Mexico City Policy. Abortion rates in HE countries started off low and trended up during Clinton’s administration and into the Bush administration until around 2007, when there was a slight decrease. The only consistent pattern is that abortion rates in both LE and HE countries rose sharply under the Obama administration, which seems to directly contradict the authors’ implications about the policy’s effects.

This lack of correlation is obscured in the main paper, because the authors focus on differences between abortion rates among HE and LE countries. Here is how they put it:

Our regression estimates show that relative to women in low-exposure countries, women living in high-exposure countries used less modern contraception, had more pregnancies, and had more abortions when the policy was in place compared with when the policy was rescinded…when US support for international family planning organisations was conditioned on the policy, coverage of modern contraception fell and the proportion of women reporting pregnancy and abortions increased, in relative terms, among women in countries more reliant on US funding.

Now it is true that abortion rates of HE countries were more similar to the LE countries under Obama then they were under Bush, but Brooks et al don’t mention that this is because rates for both groups sharply increased after plateauing at lower levels during the Bush years. There also was a larger gap in contraception use between LE and HE countries under Bush, but this gap narrowed years before Obama reversed the Mexico City policy.

The Supplemental Material contains another important chart (Figure S3). The authors color code the abortion rate per 10,000 woman-years in each African country studied for the study’s time period (1995-2014). Some countries included a lot fewer data. For example, from 1995-2014, Brooks et al have only 7 years for Swaziland and 6 years for Comoros, Gambia, and Liberia. Nearly all the countries have data missing for at least some years.

Brooks et al use data from the Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS), a nationally representative household survey. These surveys track reported abortions and live births, with spontaneous abortions (miscarriages) and induced abortions categorized together. Here’s how the authors differentiated between the two:

A termination was classified as induced if it occurred following contraceptive failure, if the terminated pregnancy was unwanted… or if the woman was under age 26 years and was not married or in a union. Terminations were not classified as induced if they occurred in the third trimester, if the woman indicated that contraception had been discontinued to allow for pregnancy, or if the woman was married or in a union with no children.

As the basis for their algorithm, the authors cite this study conducted in Turkey in 1996 using DHS data from the country. Brooks et al note their own limitations with the DHS:

Abortions are often under-reported in survey data, and the DHS is no exception.

Even if abortions did go up during the Mexico City Policy and down without it (not the case), given all the uncertainties and missing data, it would be hard to draw any sweeping conclusions from these surveys. Similarly, pro-lifers should be cautious about assuming Obama’s reversal of the policy caused the apparent abortion rate jump under his administration; the jump could reflect more accurate reporting, or the abortion rates may not be reliable to begin with.

But even if all the data presented is accurate and representative, it still doesn’t support the authors’ grim picture of the Mexico City Policy. The average abortion rate of all the 26 countries studied was apparently lower when the policy was in effect under Bush than when it was rescinded under Obama.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!