Humanity has a long history of condoning infanticide

In November 2017, the digital magazine Aeon published “Infanticide,” an article giving an historical overview of the practice across cultures. Some passages jumped out at me. Here is a TikTok summary and below it is the blog post version.

For example (emphasis added):

If there’s one thing we can still agree on in this era of political polarisation, it is that the life of a child is sacred. A mass shooting, air strike or natural disaster in which children are killed is considered far worse than one that slaughters only adults. When the ethicist Peter Singer suggested that, in theory, a baby’s life might be less worthy of protection than an adult’s because its consciousness is less developed, there were irate calls for him to lose his job.

Sounds familiar.

[Read more – A Primer on Fetal Personhood and Consciousness]

Across time and culture, human societies have widely practiced infanticide.

The author, Sandra Newman, argues that while some believe the instinct to protect our young is an evolutionary imperative, there are quite a few examples in the animal kingdom suggesting otherwise. In circumstances that threaten survival, other species will not only kill their young but even eat them.

Across time and cultures, humans have also widely practiced infanticide when there are concerns about survival – whether that be the baby’s survival, or survival of a family or community with limited resources. Newman lists four consistent factors contributing to higher infanticide rates:

- If the baby is deformed or premature

- If the mother already has other children

- If the baby is illegitimate

- If the baby is a girl

Again, emphasis added:

Sickly or deformed babies have always been vulnerable to infanticide for the same reason, and many cultures have a comforting superstition that they aren’t real humans; in medieval Europe, they were called ‘changelings’; in Africa, ‘witch babies’ or ‘spirit children’. As such, they could be abandoned or killed without guilt.

Another idea I’ve heard before. More emphasis added:

Parents ease the killing of a newborn by persuading themselves that it is not yet a child. This idea of the pre-human infant is often formalised in ritual. In ancient Athens, a child could not be killed after it had had its Amphidromia, the ceremony taking place a week after its birth, to give it a name. In early Scandinavia, it was illegal to kill a child after it had received baptism or been given food. Throughout the Christian world, baptism probably remained a cut-off point for many parents; as late as the 17th century, baptismal records often show a suspicious preponderance of male babies, with many of the girls having been quietly disposed of by their parents before they were brought to the attention of the community.

Historically infanticide was accepted or at least ignored.

Commenting on infant exposure in History of European Morals from Augustus to Charlemagne (1869), William Lecky says: ‘It was practised on a gigantic scale with absolute impunity, noticed by writers with the most frigid indifference, and, at least in the case of destitute parents, considered a very venial offence.’

In the modern American abortion debate, pro-choice people sometimes opine about how they think they would behave if they believed, as pro-lifers claim to believe, that abortion is killing valuable human beings. But I think most pro-choice people aren’t conceptualizing what it’s like to watch a human rights atrocity that is legal, widely socially accepted, and vehemently defended.

We don’t really have to imagine how most people react to such situations. Of those who don’t actively defend the problem, many look the other way. In this Aeon article, we see that even killing actual born babies has historically often been accepted or at least ignored.

If people do face a human rights issue squarely, they usually find ways to fight within accepted social systems, because stepping too far outside those norms often gains little while costing a lot. (There are many examples of this approach with American abolitionism, such as mailing campaigns and legislation allowing for gradual change.) Infanticide appears to have been no exception, with communities often looking the other way or, if they did enforce legal repercussions, softening the blow:

Often, societies treat neonaticide as not-quite-murder. In many legal systems, the killing of a neonate by its mother is a crime distinct from homicide, and punished less harshly, while the murder of a baby by its father is not.

This passage echoes some of the ongoing discussion about legal repercussions for women who seek abortion. Even with born babies, historically societies have taken a more subdued approach to penalties for infanticide than other kinds of homicide, perhaps in recognition of the conflicts and pressures of pregnancy and the postpartum period.

[Read more – Why penalties for illegal abortion should not focus on the woman]

None of this is to say society was indifferent to child killing. On the contrary, Newman discusses the parental need to first dehumanize newborns destined to be killed, as well as society’s preference to talk about the phenomenon only as “a rare and shocking crime, or a heinous practice of foreigners, even when it is actually a perennial occurrence in their own neighbourhoods.” Infanticide was horrific enough people resisted acknowledging it.

In the 1700s the foundling hospital movement started attempting to solve the problem, but with minimal success. Per Newman, infanticide rates didn’t begin to really drop until the popularization of condoms. “We stopped killing our babies only when we started having fewer of them.”

There are competing ideas about how infanticide relates to abortion.

Newman speculates that infanticide could make some comeback with efforts to make abortion illegal coupled with restricting access to birth control. This sounds similar to the arguments some abortion advocates make that laws against abortion will paradoxically cause abortion rates to increase. They usually point to research suggesting that restrictions on contraception can lead to higher unintended pregnancy rates and thus higher abortion rates, and they argue that regimes known for restricting abortion often also have more restricted contraception access.

But the two don’t have to go hand in hand. In fact, multiple U.S.-based studies have found that abortion restrictions on their own are associated with greater uptake of contraception and thus lower unintended pregnancy rates. It’s probable that efforts to make abortion illegal, if coupled with the same or greater access to birth control, would decrease not only abortion rates but also unintended pregnancy rates, and thus infanticide.

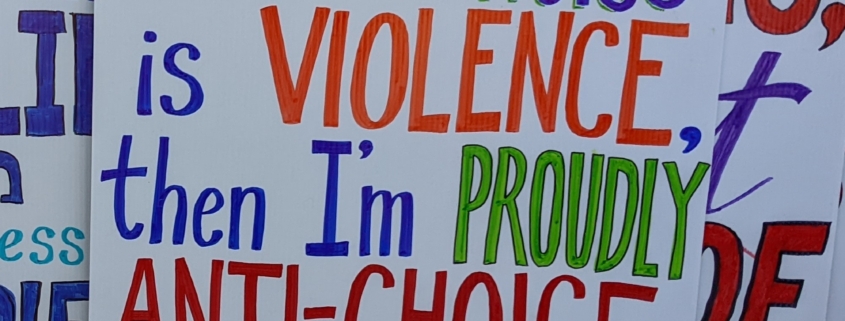

Meanwhile, arguments to justify abortion often flirt with justifying infanticide. We see this with calls for legal elective abortion even in the third trimester, arguments that not all humans are persons with the right to life (particularly arguments that rest personhood on cognitive function), and even direct calls for a softer approach to infanticide itself (search this page for the phrase “defective infant”).

[Read more – After-birth abortion: why should the baby live?]

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!