Are doctors afraid to manage miscarriages because of abortion bans?

There have been many news articles implying or outright claiming that abortion bans have made doctors afraid to manage miscarriage. Often the articles are about (1) women in states with abortion bans who (2) have a missed or incomplete miscarriage (their body does not fully pass the remains of their child on its own) and then (3) don’t quickly receive medical interventions (usually referencing D&C). Sometimes the story ends there. Other times it goes on to explain (4) the woman experiences a medical emergency and has to have emergent intervention.

The issue is not that these stories are false. Some may be, but many are certainly true. The issues are that the stories often incorrectly assume (1) delays in intervention are nonstandard and always inappropriate and (2) insufficient medical care can only be attributed to abortion bans.

There are good reasons to wait and see if intervention is necessary for miscarriage.

Doctors need to confirm the diagnosis of a missed miscarriage.

Doctors need to make sure they don’t incorrectly diagnose a missed miscarriage. If the doctor thinks there’s been a missed miscarriage and there hasn’t, an intervention (D&C, abortion pills) could kill a living and wanted embryo or fetus.

Of course there’s the risk in the other direction: if the doctor doesn’t correctly diagnose a missed miscarriage, the woman has to, at best, deal with the psychological and emotional stress of waiting to find out if she has miscarried. At worst, she risks going septic or having other medical problems.

So how do doctors try to avoid both types of errors?

The New England Journal of Medicine lists specific guidelines for ultrasound diagnosis of pregnancy failure, including:

- crown-rump length of greater or equal to 7 mm and no heartbeat

- mean sac diameter of greater or equal to 25 mm and no embryo

- absence of embryo with heartbeat two weeks or longer after a scan that showed a gestational sac without a yolk sac

- absence of embryo with heartbeat 11 days or longer after a scan that showed a gestational sac with a yolk sac

Note the criteria involve waiting between 11 days and two weeks after an initial concerning scan to reassess.

The document also lists findings that are “suspicious for, but not diagnostic of” pregnancy failure:

- crown-rump length of less than 7 mm and no heartbeat

- mean sac diameter of 16-24 mm and no embryo

- absence of embryo with heartbeat 7-13 days after a scan that showed a gestational sac without a yolk sac

- absence of embryo with heartbeat 7-10 days after a scan that showed a gestational sac with a yolk sac

- absence of embryo 6 weeks or longer after the last menstrual period

- empty amnion (amnion seen adjacent to yolk sac, with no visibile embryo)

- enlarged yolk sac (more than 7 mm)

- small gestational sac in relation to the size of the embryo (less than 5 mm difference between mean sac diameter and crown-rump length)

The guidelines state

When there are findings suspicious for pregnancy failure, follow-up ultrasonography at 7 to 10 days to assess the pregnancy for viability is generally appropriate.

“Diagnostic Criteria for Nonviable Pregnancy Early in the First Trimester,” Doubilet et al

Again, it is standard to recommend waiting and then reassessing a pregnancy to confirm there has actually been a miscarriage.

D&Cs come with their own risks and need to be medically indicated.

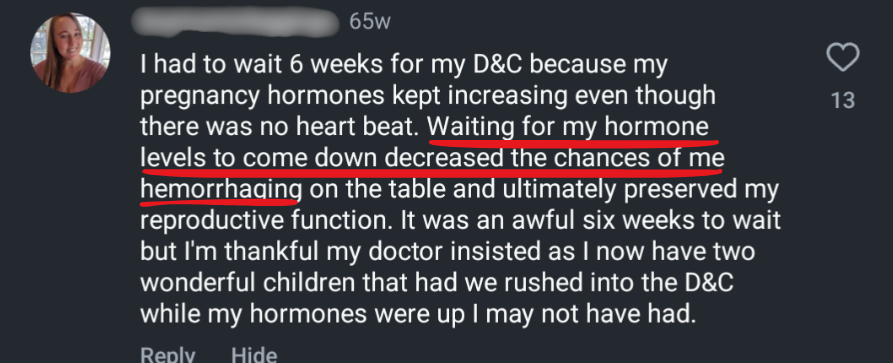

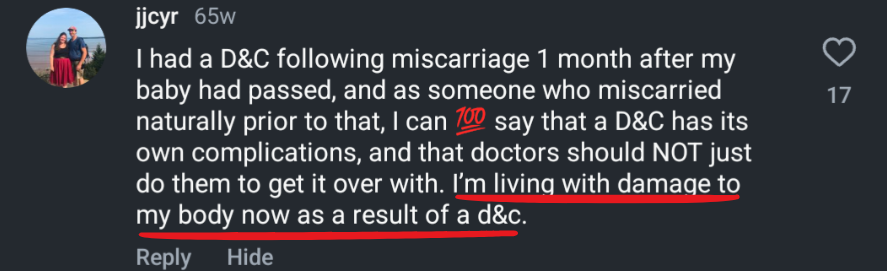

Even when a missed miscarriage is correctly diagnosed, doctors may recommend waiting to intervene to give the woman’s body a chance to pass the remains on its own. D&C is a medical intervention that comes with its own risks. According to the National Library of Medicine, complications from D&Cs can include infection, bleeding, cervical lacerations, uterine perforation, and postoperative uterine adhesions.

These complications are all unusual, and D&Cs are performed without complication most of the time. However a doctor assessing the safest options for a patient compares risks and complication rates of intervention (in this case, D&C) with risks and complication rates of not intervening (in this case, waiting to see if a woman passes the remains naturally). In many cases, doctors believe not intervening is the more prudent approach.

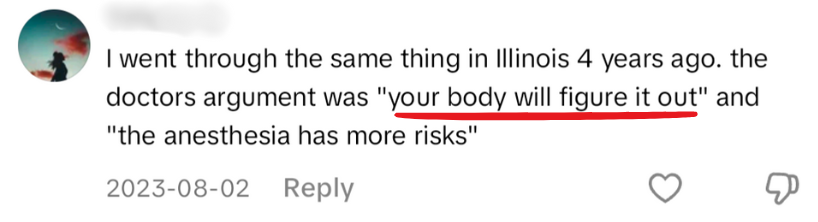

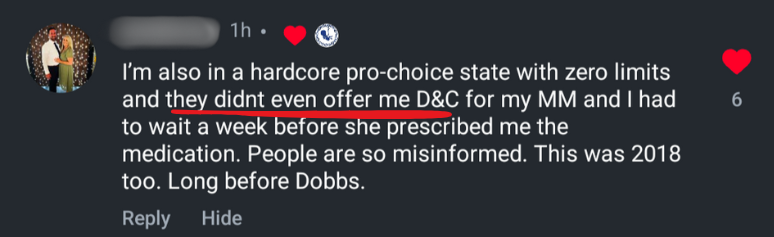

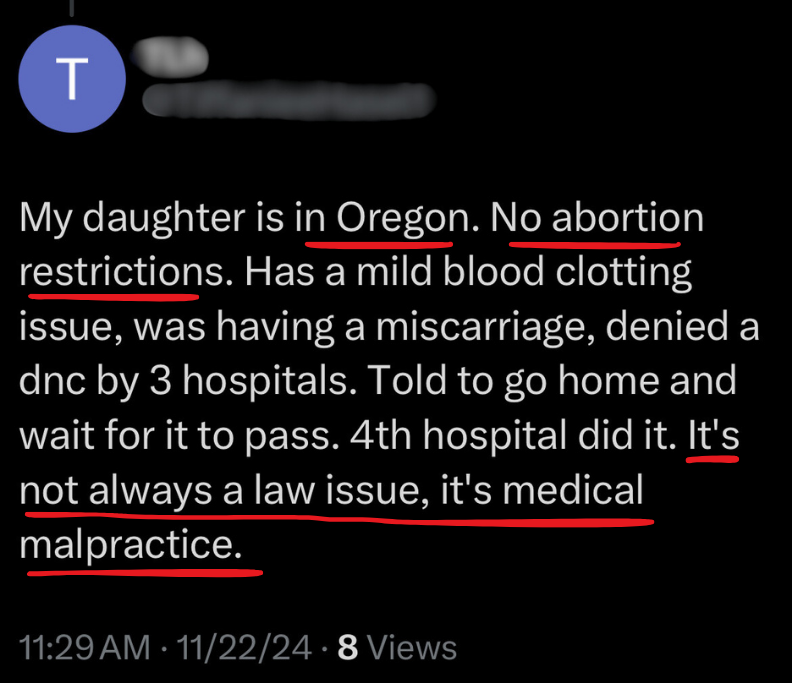

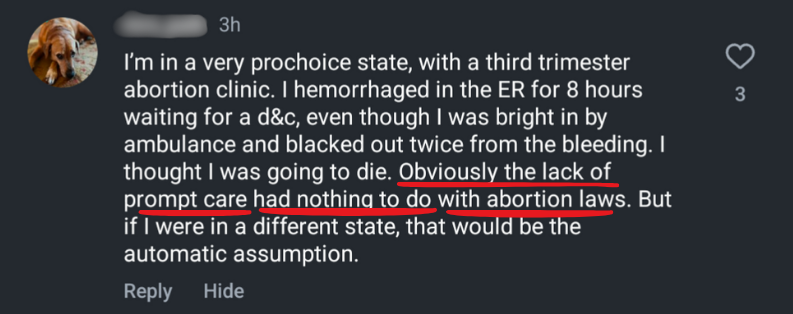

Doctors in states without abortion bans will still recommend waiting before intervening.

These considerations can explain why doctors in states without abortion bans (either pro-choice states now or pro-life states prior to Dobbs) still recommend waiting before intervening in miscarriage cases. (We saw this in the case of Christina Zielke, whose story was written to suggest Ohio was denying miscarriage care due to abortion laws. Zielke’s OB in Washington DC had recommended she wait to pass remains from her missed miscarriage naturally, rather than getting abortion pills or a D&C.)

Clearly abortion restrictions are not the only reason a doctor would decline to offer D&C or abortion pills, given doctors decline to do so in places and times without abortion restrictions. Yet the journalists describing these situations rarely discuss the other possible reasons a doctor would not intervene.

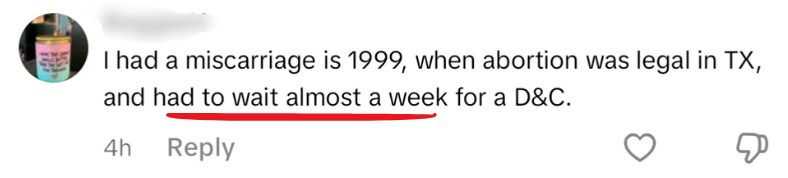

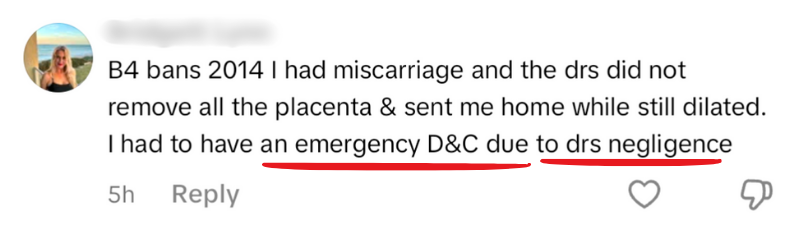

Poor miscarriage management can also happen due to mistakes, medical negligence, or medical malpractice.

The United States has one of the poorer maternal mortality rates of first world countries, and the CDC has determined most maternal mortality cases are preventable. These problems are not limited to states with abortion bans.

[Read more – Doctor delayed emergency care for my ectopic pregnancy…in pro-abortion New York.]

There are many factors that can contribute to maternal mortality. Some examples:

- misdiagnosis/delayed diagnosis

- failure to recognize pregnancy-related complications

- errors in medication (wrong medications, wrong dosages, dangerous interactions with other medications or conditions)

- lack of informed consent (many topics, including contraception, fertility treatments, miscarriage prevention, handling of fetal remains, options for childbirth, pain management)

- inadequate monitoring post childbirth or post-gynecologic procedures

- dismissal of seriousness of pain or other symptoms

- miscommunication within members of a medical team

- poor communication between medical team and patients

Any of these and others can lead to errors. But it’s more difficult for the medical community or society to identify and mitigate these problems if we try to fit all healthcare failures into a narrative about abortion bans. (tweet this)

The case of Neveah Crain is an infuriating example of this problem. ProPublica tried to blame Crain’s death on Texas abortion laws, despite the obvious evidence of unforced, egregious medical malpractice. About a week after ProPublica published their story, Neveah Crain’s family told a local news agency that Crain’s death was “being used for politics” and that they want the hospitals to pay for negligently killing her.

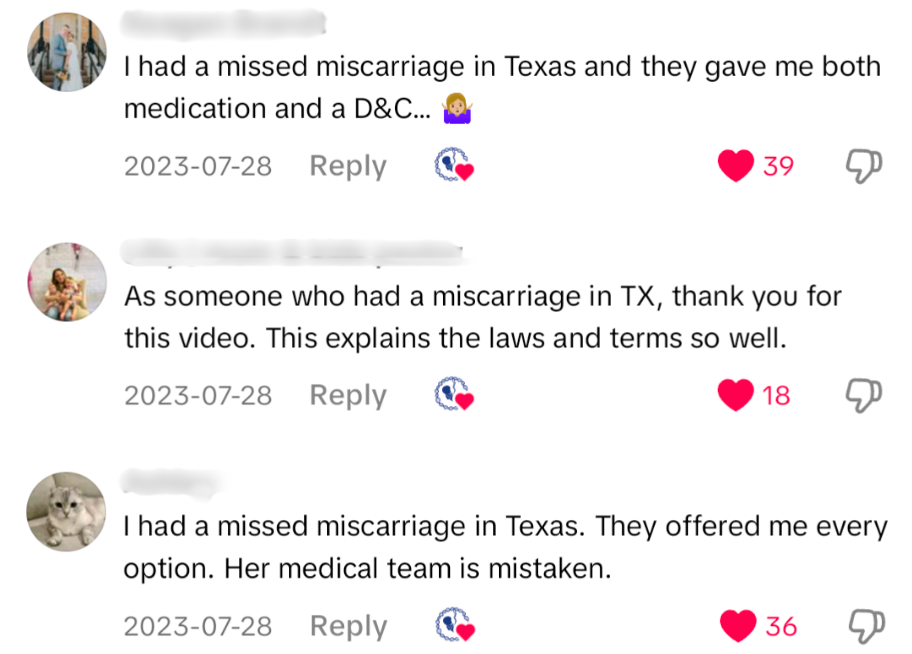

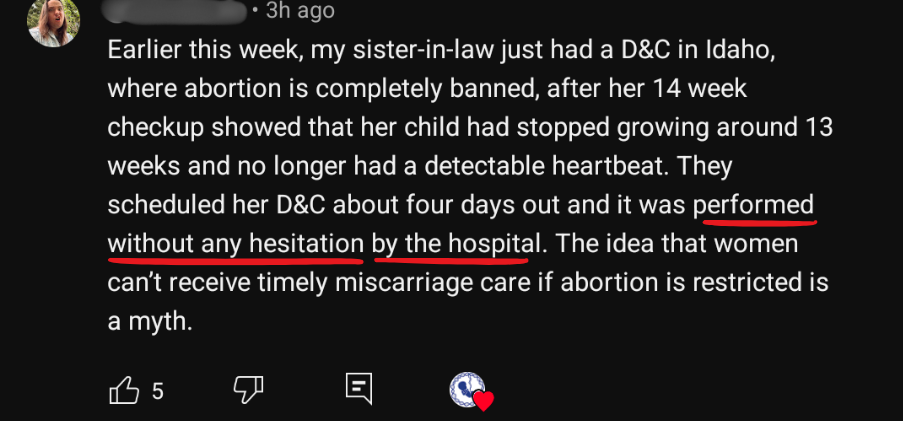

Doctors in states with abortion bans are still managing miscarriage appropriately.

Despite the existence of medical malpractice (in both pro-life and pro-choice states), most doctors are providing appropriate miscarriage care.

We don’t read stories about women who receive appropriate care in ban states, although those stories dramatically outnumber the cases of denied care. We know this because we know:

- there are roughly 1 million miscarriages per year in the US

- roughly 15-20% of them are missed/incomplete miscarriages

- which means midpoint of 175,000 missed miscarriages a year in the US

We can estimate how many such cases happen in each state based on the state’s percent of the national population. For example, Texas has about 9% of the US population, so we’d expect about 15,750 missed miscarriages every year in Texas. (Again this is not total miscarriages; it’s only those in which the woman doesn’t pass the remains on her own.) How many times a year, then, are Texan doctors offering miscarriage management without incident?

The media trumpets individual stories of denied care in ban states. These articles are often nonsense, but even if we assumed they were portraying events accurately, they would still be misleading the public because of which stories they choose to cover and which they don’t.

These articles don’t mention counter examples such as denied care in pro-choice states or appropriate care in pro-life ones. They don’t discuss other possible causes of medical negligence. The journalists aren’t trying to investigate first and let evidence lead them to their conclusions. They are certain of a conclusion to begin with: that laws protecting embryos and fetuses are causing harm to women. And then they write these stories to support that conclusion, regardless of evidence.

[Some of this content is available on Instagram here.]