Fertility awareness and pro-choice feminism: a perfect union, or at odds?

Photo Credit Virginia Pride

The words “fertility awareness” may invoke different responses from people, depending on what the person has actually been told about it. For some, it is (erroneously) viewed as the outdated Calendar Method – an unreliable form of birth control that gets you pregnant more than it doesn’t. Others may have heard of fertility awareness, and have a vague idea of cycle tracking for health reasons, typically involving an app. Very few understand fertility awareness for the body of knowledge that it is, pro-choice activists included.

Laury Oaks knows that most in the pro-choice feminist movement view fertility awareness as either unreliable, or so rife with religious, anti-choice rhetoric that utilizing it in any way is a threat against bodily autonomy. However, a growing subset of pro-choice activists like Oaks have been drawn to the body literacy that fertility awareness provides, which is why she recently published “Feminist Fertility Awareness? Sexual and Reproductive Knowledge in a Post-Roe World” in the Journal of Women in Culture and Society.

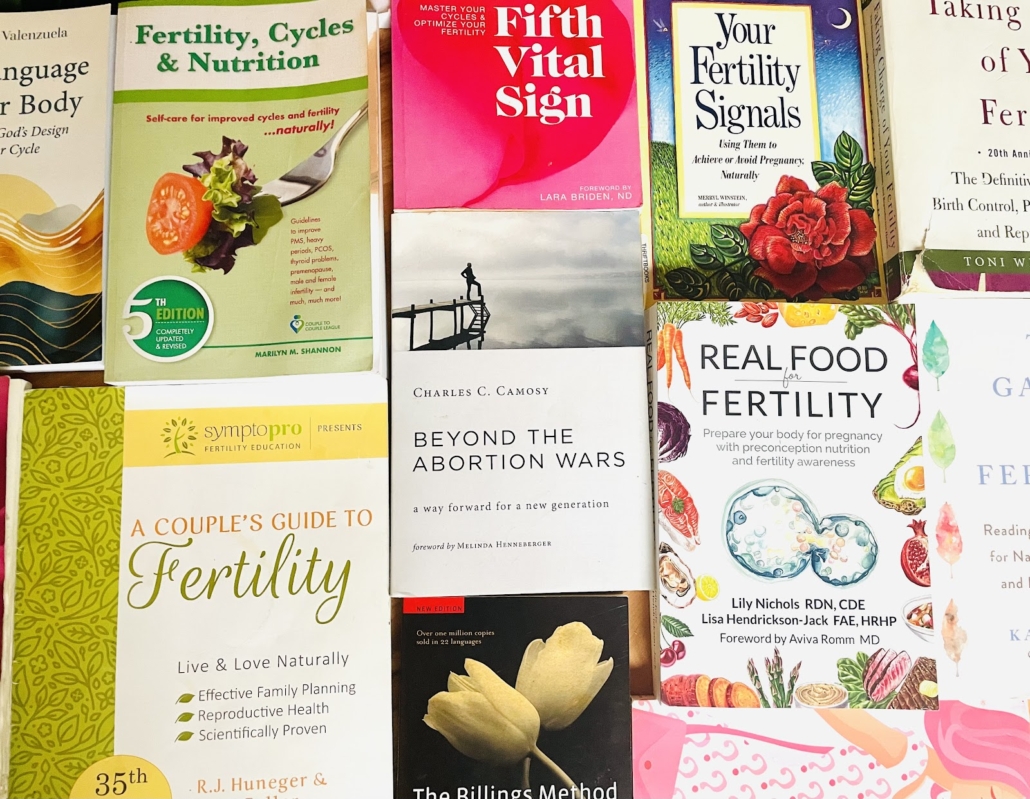

Fertility Awareness 101

Before we delve into the pro-choice view of fertility awareness (henceforth referred to as FA), we must define what FA even is. FACTS About Fertility, a leading medical organization on the research and training for fertility awareness in medicine, describes FA in their patient handout:

[W]ith Fertility Awareness Based Methods (FABMs), a woman can learn to observe various physical signs, or biomarkers, that reflect the hormonal changes in her monthly cycle[.] A woman may record these observations on a paper chart or track them using an app to monitor her health and understand her body better. With this information, a woman or couple can identify potential fertile days as well as note infertile days to plan or prevent pregnancy. Charting data also provides valuable information that may help trained medical professionals diagnose and manage common women’s health concerns.

FACTS also goes on to describe what these biomarkers are:

Almost all FABMs rely on observations of one or more biomarkers, including cervical fluid, basal body temperature, and urinary hormones.

More simply put, tracking even just one biomarker can allow a woman to know which day in her cycle could lead to pregnancy, should she have unprotected sex. By using this information, she can choose to either abstain during her fertile days, or utilize a barrier method to prevent pregnancy. These same biomarkers can also be utilized by specifically trained professionals to diagnose, treat, and properly time tests/medications for conditions including but not limited to PCOS, endometriosis, thyroid disease, menorrhagia, dysmenorrhea, and the various causes of infertility.

Please refer to the links above to learn more about these methods, their applications, and their effectiveness rates.

Fertility Awareness as Empowering Body Literacy

It is not surprising, then, that people of all backgrounds (including pro-choicers) find FA alluring in its ability to educate and empower people with the ability to treat female-specific conditions, and to also prevent pregnancy without side effects.

In fact, pro-lifers (typically religious) have been advocating and teaching FA for decades. Women who are against abortion especially appreciate that the FA methods do not have the risk of preventing implantation, or harming the embryo/fetus, should accidental pregnancy occur. This, they claim, is unlike hormonal methods and (potentially) copper IUDs, which have the potential to do both.

(Note: Keep in mind that the Pro-Life Movement is diverse, and not all pro-life people are against the use of some or all contraceptive methods. SPL as an organization supports the use of all contraception, and does not believe there is enough evidence to support that certain methods like the pill or IUD are truly abortifacient. The studies are mixed on this information, and SPL understands if some readers come to different conclusions.)

So what is Oaks’ take on FA? Is FA a common ground for both pro-choice and pro-life people to meet on and make real changes for the betterment of all, or is this a further point of contention?

Fertility Awareness and Inclusive Feminism

The foundation of Oaks’ paper is simple. As she explains:

I focus on feminist framings of this lesser-known, nonhormonal contraceptive practice. Fertility awareness methods can enhance body knowledge – even sexual liberation – beyond political, legal, medical, or religious institutions.

She also explains that her analysis “draws on scholarship and advocacy by the Black women’s health, global human rights, and women of color reproductive justice movements,” and how bodily autonomy is affected by various forms of bigotry, including, “racism, sexism, heterosexism, classism, and ableism.”

Throughout the paper, Oaks goes over the brief history of FA from the 1960s onwards, and discusses the involvement and limitations of different FA proponents. Based on her foundational framings, she compares and contrasts each branch of FA’s advocacy to test their involvement and inclusion of LGBT, feminism, and especially abortion support. These options range from religious and/or pro-life educators, to nominally pro-choice educators, and to people and organizations who are unapologetically pro-choice and vocal about social injustices. She makes many claims, based on other feminist writings, about how pro-life and/or religious FA educators are not sufficient options for the public at large, leaving a niche for the secular, pro-choice educators to take the reins.

SPL is in agreement with Oaks on the importance of contraception access, sexism, racism, ableism, homophobia, and other topics as legitimate social concerns. This article will focus on FA and abortion support, specifically, as we go over Oaks’ paper.

Fertility Awareness Proponents and Their Abortion Support (or lack thereof)

Oaks begins with a scathing critique of the religious and pro-life influence of today’s FA organizations. Due to the papal encyclical Humanae Vitae, which forbids birth control use but condones natural family planning (a religious term for FA), the first FA organizations, researchers, and educators were Catholic. From there, religious philosophies underpinned much of the FA movement from the beginning. While she points out the hypocrisy of pro-abortion organizations mocking the growing availability of FA in a post-Roe world, she also believes that pro-life advocates are taking advantage of women who are frustrated with other methods of contraception, and may be “at risk” of seeking services with antiabortion organizations. By default of lacking this inclusivity, Oaks argues, they will be unable to provide women with an unlimited range of reproductive healthcare and education.

In tandem, feminists warn that antiabortion [and religious] networks have sought to appeal to women, particularly those dissatisfied with hormonal methods, and convince them that fertility awareness is the safest, most natural, and best option to prevent pregnancy.

Examples cited on this phenomenon include FEMM Health, the Guiding Star Project, and Obria. They are secular in the sense that they do not push a religious worldview, nor do they use religious arguments to support their FA philosophy. However, they also employ or receive funding from religious entities that, Oaks argues, are problematic. These and others, Oaks claims, will, “…disrupt the public trust invested in mainstream contraception… Exposing antiabortion strategies is necessary so that anyone seeking sexual and reproductive health information or care is respected and able to provide full, informed consent.”

In contrast to these “infiltrators,” Oaks then goes on to discuss inclusive options that support abortion. These options include Justisse Healthworks, an organization that is upfront about their support to abortion access. Ilene Richman is also applauded by Oaks for her inclusive nature as a fertility awareness educator, who is quoted to say, “I support ALL reproductive health choices; my goal is to help you make the ones that are best for you.”

Infiltration, or Genuine Healthcare?

If this argument of “antiabortion infiltration” bringing in “disruption” to the healthcare system sounds familiar, it’s because it is. It’s a common tactic to attack pro-life responses to medical and societal problems as being insufficient due to refusing to enable elective abortion. The same argument has been made against Crisis Pregnancy Centers/Pregnancy Resource Centers ever since their inception (something that Oaks also briefly criticizes in her paper). CPCs and PRCs have been addressed before by SPL, discussing the biased views that pro-choice researchers hold about PRCs but also touching on the researchers’ appreciation for the niche work that PRCs can provide:

Kimport implores policy makers and pro-choice activists to approach the reality of PRCs holistically: recognizing that they are giving resources to pregnant women lacking elsewhere…

Another SPL article showcases how women considering abortion are more likely to choose life if they go to a CPC. This is because, “[p]regnant people have obtained material resources and emotional support at CPCs, which may have played a role in encouraging them to continue the pregnancy.”

CPCs and PRCs provide a life-affirming service to women who may not find it elsewhere – even in so-called “inclusive” pro-choice settings.

Likewise, pro-life fertility awareness advocates offer family planning services, education, and support that suits the needs of women and families who are not likely to find these services in self-proclaimed pro-choice organizations or people. Giving a wanted and needed service to people is not “infiltration,” but genuine problem-solving that utilizes the skills of pro-life advocates.

Pro-Life Healthcare is Genuine Healthcare

One wonders how Oaks defines “infiltration.” Is it intentionally deceiving the public in order to “trick” them into a life-centered health service? Or is it as simple as a pro-life professional interacting with potential patients and clients in order to provide them with services that they are seeking?

Pro-life healthcare is nothing new. In fact, there is not only a long history of pro-life healthcare workers from around the world, but they are very much an active and necessary part of the industry today. A large part of their necessary interaction with the public is because the public itself is in need of their life-affirming practices:

Half of women and nearly half of men in the United States are pro-life and they all exist as patients in our modern-day health care system. Like everyone else in our nation, they suffer from heartbreaking health problems such as infertility, recurrent pregnancy loss, and other medical trauma; and no doubt many of them have a child, other family member, or friend who is disabled or chronically ill. Their pro-life viewpoints most certainly inform them of the holistic, whole-life care that they and their loved ones deserve, of the dignity due to them when receiving medical care.

Abortion support often comes hand in hand with ableism, sexism, and other forms of bigotry that Oaks discusses within her paper. Pro-life professionals and paraprofessionals offer a unique solution to these problems, based on the belief that all people from conception to natural death are worthy of legal and ethical protections. When “inclusive” pro-choicers actively fight these efforts, they hypocritically do great harm in denying necessary and wanted resources to the people they claim to speak for.

Fertility Awareness as a Middle Ground

It is reality that inclusivity cannot possibly include all people at all times. This isn’t to say that a pro-choice educator is unable to help a pregnant client find resources on financial aid, or that a pro-life educator is nothing but callous to post-abortive women seeking help with their cycles. Individuals are more nuanced and caring than we give them credit for.

However, Oaks misses an opportunity to reach out to pro-life fertility awareness users in a combined effort to prevent unplanned pregnancies that may lead to abortion. Especially because abortion access may cause less rigorous use of birth control, fertility education can help reduce abortion numbers and increase safe sexual decision making, by simply educating the public on how and why they become pregnant to begin with.

As a fertility doula myself, I understand the necessity of promoting prudence in family planning and reproductive health. I agree with my pro-choice counterpart, Suzannah Doyle, when she says in Katie Singer’s book The Garden of Fertility that she is “pre-choice”:

If people – including teenagers – know their fertility signals, they’re more likely to make informed, responsible choices about sex.

While we fundamentally disagree on the equity of the unborn, we can meet in the middle even in a Post-Roe world, one in which women and men have the ability to make safe, informed, and educated decisions with their bodies regardless of abortion access. FA may not end the abortion debate, but it can help forge a future where our fertility is no longer feared and abhorred. Rather, FA can be the touchstone needed to educate the public on their responsibility towards sex, their bodies, and one another – including the unborn they could potentially conceive.

While advocates like Oaks are wary of pro-life educators, I reach out my hand in understanding. All people, everywhere, have a right to be educated on body literacy through FA. I will never turn down an opportunity to build bridges with those willing to walk across it with good intentions.