A Legal History of Induced Abortion in the United States

A recurring flaw with modern claims about induced abortion legality in early America is that they are seen through the lens of modern medicine. However, in the eighteenth century, there were no ultrasound images, no fetal stethoscopes, no home pregnancy tests, and really no way to reliably confirm pregnancy until a woman could feel movement of the unborn child within the womb – the “quickening.”

The science of embryology did not yet exist. Both the oocyte and the spermatozoon were still foreign concepts. The point at which individual life began was more a philosophical concept than one of medicine and biology. Law at the time reflected this state of contemporary medicine, commonly treating quickening as the demarcation for criminality. Before that threshold, little was understood; after it, the woman was seen as “pregnant with child.”

For this reason, it is undeniably flawed for abortion proponents to use the 1736 John Tennent book Every Man His Own Doctor [1] to support their views. In its American reprint, publisher Benjamin Franklin would have seen the included recipe for “suppression of the courses” to be remedies for irregular menstruation — rather than potentially abortifacients.

English common law had focused for centuries on quickening for the vast majority of crimes. Third-parties causing miscarriage before quickening may treat pregnant women as the victims of misdemeanors, while crimes after quickening were considered homicidal acts against the unborn children.

Founder and Declaration of Independence signatory John Witherspoon gave a lecture series at Princeton on moral philosophy. One lecture covered the “Relation of Parents and Children” [2]. In this, he rebuked those who viewed children as property to be discarded (original emphasis retained):

Some nations have given parents the power of life and death over their children; and Hobbs insists, that children are the goods and absolute property of their parents, and that they may alienate them and sell them either for a time or for life. But both these seem ill founded, because they are contrary to the end of this right, viz. instruction and protection. Parental right seems in most cases to be limited by the advantage of the children.

Induced abortion – that “power of life and death” – was considered a heinous act. Thomas Jefferson echoed the sentiment in his 1787 book, Notes on the State of Virginia [3], about a practice by the Cherokees, he saw as barbaric, contributing to their low population growth:

The women very frequently attending the men in their parties of war and of hunting, child-bearing becomes extremely inconvenient to them. It is said, therefore, that they have learnt the practice of procuring abortion by the use of some vegetable; and that it even extends to prevent conception for a considerable time after.

William Blackstone, Solicitor General to the Queen of England, wrote of induced abortions and fetal homicides in his 1765 English common law compendium, Commentaries on the Laws of England [4]:

Life is the immediate gift of God, a right inherent by nature in every individual; and it begins in contemplation of law as soon as an infant is able to stir in the mother’s womb. For if a woman is quick with child, and by a potion, or otherwise killeth it in her womb; or if any one beat her, whereby the child dieth in her body, and she is delivered of a dead child; this, though not murder, was by the antient law homicide or manslaughter.

Founder and US Supreme Court Justice James Wilson gave a lecture series on law to President George Washington and his cabinet in 1790. One such lecture, “Of the Natural Rights of Individuals,” [5] discussed American inheritance of English common law:

With consistency, beautiful and undeviating, human life, from its commencement to its close, is protected by the common law. In the contemplation of law, life begins when the infant is first able to stir in the womb. By the law, life is protected not only from immediate destruction, but from every degree of actual violence, and, in some cases, from every degree of danger.

In 1803, Lord Ellenborough’s Act [6] in the United Kingdom created early statutory law related to induced abortions, clearing up ambiguities in common law. While it still used the quickening as demarcation, it declared abortions induced before or with unproven quickness to be felonies with convictions resulting in fourteen years imprisonment. Post-quickening induced abortions were capital crimes equal to murder.

On the medical front, it became common for early nineteenth century physicians to denounce as quacks those who induced abortions. Dr. Samuel Akerly wrote of coercive abortionists in The Medical Repository (1808) [7]:

Many inert remedies are no doubt rendered efficient and powerful in the hands of these illegitimate sons of Esculapius, by the force of recommendation and the power they have over the minds of their patients.

In the coming years, scientists and physicians began questioning the validity of the quickening. Dr. John Burns expressed such reservations in Burns’s Obstetrical Works (1809) [8]:

…I must remark, that many people at least pretend to view attempts to excite abortion different from murder, upon the principle that the embryo is not possessed of life in the common acceptation of the word. It undoubtedly can neither think nor act; but upon the same reasoning, we should conclude it to be innocent to kill the child in the birth.

Whoever prevents life from continuing, until it arrive at perfection, is certainly as culpable as if he had taken it away after that has been accomplished.

Dr. John Beck, vice-president of The Medico-Chirurgical Society, went a step further and expressed absurdity of the quickening in his 1817 work, An Inaugural Dissertation of Infanticide [9]:

In modern times, an error no less absurd, and attended with consequences equally injurious, has received the sanction, not merely of popular belief, but even of the laws of the most civilized countries. The error consists in denying to the fœtus any vitality until after the time of the quickening. The codes of almost every civilized nation have this principle incorporated into them, and accordingly, the punishment which they denounce against abortion, procured after quickening, is much severer than before.

In the United States, statutes began arising to clarify ambiguities left in common law. They often mirrored the text of Lord Ellenborough’s Act, focusing on methods of inducing abortions that involved the ingestion of drugs or poisons. The first was legislation came in Connecticut in 1821 [10], in direct response to the weak sentencing after the politically-motivated case against preacher Ammi Rogers [11]. Missouri [12] and Illinois [13] followed with similar statutes (covering the entirety of pregnancy) in the next few years.

The entire state of medicine changed in 1827 with the publication of Karl Ernst von Baer’s Ovi Mammalium et Hominis Genesi [14]. This book shared with the world the discovery of the mammalian ovum. He followed the next year with the comparative embryology book Über Entwickelungsgeschichte der Thiere [15]. These works were so groundbreaking that von Baer is now often called “the father of embryology.”

Immediately, lawmakers in the United States took notice. Within the next decade, pre-quickening statutes on criminal abortion came in New York (1828) [16], Ohio (1834) [17], and Indiana (1835) [18].

Additionally, legislatures of Georgia (1833) [19] and Arkansas (1838) [20] enacted statutes to suspend death sentences for pregnant women until they had given birth.

In the United Kingdom, the 1837 Offences Against the Person Act [21] completely removed any mention of the quickening, something that would soon resonate within the United States.

The Supreme Court of Pennsylvania expressed the rapidly-changing view of the quickening in the 1846 case, Commonwealth v. Demain (1 Brightly 441) [22]:

It is a flagrant crime at common law to attempt to procure the miscarriage or abortion of a woman… It is not necessary, in such an indictment, to aver quickness on the part of the mother; it is sufficient to set forth that she was “big and pregnant.”

By mid-century, the stethoscope came into common use, allowing detection of a fetal heartbeat long before many women felt fetal movements. This combined with general advances in medicine led many physicians and medical associations to more directly denounce the growing underground abortion industry.

In 1854, obstetrician Hugh Hodge gave a lecture at the University of Pennsylvania called “On Criminal Abortion,” [23] in which he spoke of the absurdity of the quickening:

What, it may be asked, have the sensations of the mother to do with the vitality of the child? Is it not alive because the mother does not feel it? Every practitioner of Obstetrics can bear witness that children live and move and thrive long before the mother is conscious of its existence; and that women have carried healthy children to the seventh, and even to the ninth month without being conscious of its motions.

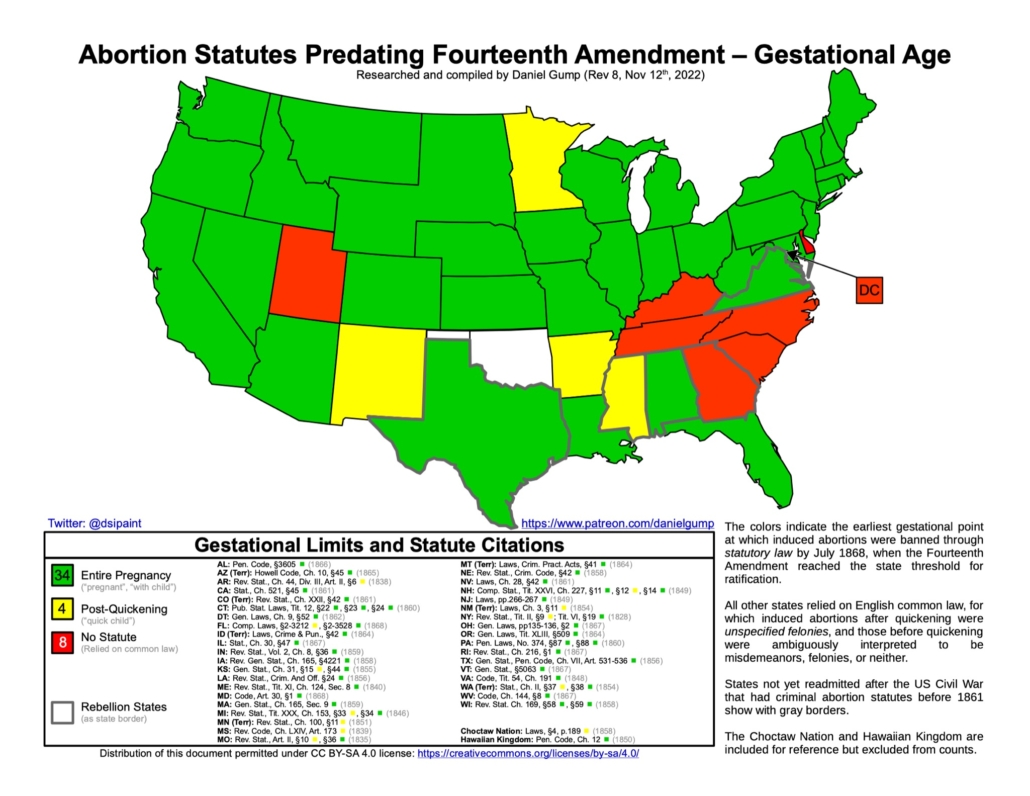

By the mid 1850s, more than half of states and territories had criminal abortion statutes, the majority of which defined pre-quickening criminality.

In 1857, the newly-founded American Medical Association convened for a conference in Louisville, Kentucky. Under the leadership of obstetrician and pioneer gynecologist Dr. Horatio Storer, the Committee on Criminal Abortion formed to research the rapidly-growing underground industry. Their report [24] two years later declared (1) there to be widespread ignorance among the general public on induced abortions, (2) a state of carelessness by physicians that leads to unintentional fetal demise, and (3) a failure of laws to recognize civil rights of the unborn. The committee unanimously condemned the crime of abortion and called for (1) educating the general public on fetal development, (2) correcting errors of negligence within their ranks, (3) establishing an obstetrics code, and (4) lobbying efforts for laws to better protect the unborn.

On his own, Storer also wrote and published a number of books and essays regarding criminal abortion [25], fetal development [26], and improved obstetric and gynecological practices.

State medical associations led their own efforts, as well. The Maine Medical Association declared in their 1866 “Report on Production of Abortion” [27] that inducing abortion at any gestational age is morally equivalent to murder. The report included a quotation from Chief Justice John Tenney of the Maine State Judicial Court stating, “the reference to the quickening of the child seems to rest upon no reasonable grounds, and has been abandoned by jurists in all countries where enlightened jurisprudence exists in practice… the procuring of abortion must be treated as a species of murder.”

It was common for these reports to declare that modern medicine had even eliminated any potential necessity to induce abortion to save the mother’s life. Dr. Ed Le Prohon wrote in his 1867 essay “Voluntary Abortion” [28] that the skull-crushing craniotomy abortion was more dangerous in medical emergencies for the mother than Caesarian sections, and Storer had spoken of the horrors of infants surviving such barbaric abortion procedures. Thus, Prohon declared that less-experienced — or even fraudulent — physicians were the only ones to perform them:

So long as a physician will parade the opinion that he has the power of destroying a child because he thinks that the life of the mother is in danger, so long will premature labor be provoked by unscrupulous practitioners and quacks, and so-called midwives, and even mothers will not neglect to adopt this easy method, to suit their inclinations.

During this timespan of the 1850s to 1860s, many state legislatures eliminated references to the quickening in statutes, expanding their former post-quickening laws to cover the entirety of gestation. Among these, Ohio’s 1867 Journal of the Senate [29] included a detailed committee report with the passage:

The erroneous opinion has been entertained by the unthinking – and our law has favored the idea – that the life of the fœtus commences only with quickening, and hence the conclusion that to destroy the embryo before that period is not child-murder, but only a venial offense. No opinion could be more erroneous. Quickening is generally purely mechanical. The uterus, in consequence of its enlargement, rises from the cavity of the pelvis to that of the abdomen. Hence the sensation of motion.

By the close of the American Civil War, nearly all states and territories had criminal abortion statutes, and about three-quarters of those criminalized the acts before the quickening. [30] Most remaining hold-outs were former Confederate states that would go on to enact their own statutes in the coming decades, when overhauling their legal codes. Every state had criminal abortion statutes by the early twentieth century.

Clearly, the nineteenth century was one of rapid scientific advancements in areas that included embryology, obstetrics, gynecology, and medical technology. With these changes came greater understanding of prenatal development that expanded into the legal realm and relegated the premise of the quickening into the pseudoscientific realm. As common law could not keep pace with rapid changes, statutory law overtook it as the means of defining criminality of induced abortions.

From a twenty-first century vantage point, one can lose perspective of just how much changed in such little time, providing the foundation for concepts that seem elementary by today’s standard. Yet, historical evidence shows that from the founding of the United States, the intent was always to protect the lives of unborn children from the moment their existences became known. Thus, to argue today that induced abortions are not killing living human beings, one must rely on science that has been outdated for nearly two centuries.

[Today’s guest article is by Daniel Gump.]

—

- Tennet, John. (1736) “Suppression of the Courses,” Every Man His Own Doctor, 4th Ed. pp.40-41. Philadelphia: Benjamin Franklin. https://archive.org/details/every-man-his-own-doctor-the-poor-planters-physician

- Witherspoon, John. (circ. 1768-1794) “Relation of Parents and Children,” Lectures on Moral Philosophy. pp.103-105. Philadelphia: William W. Woodward (1822). https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.hnnmbc&view=1up&seq=9&skin=2021

- Jefferson, Thomas. (1787) Notes on the State of Virginia, pp.100-101. London. https://hdl.handle.net/2027/nyp.33433115611448?urlappend=%3Bseq=111

- Blackstone, William. (1765) Commentaries on the Laws of England, vol.1, ch,1. p.129. Dublin. https://hdl.handle.net/2027/mdp.35112203967999?urlappend=%3Bseq=251

- Wilson, James. (1790) The Works of the Honourable James Wilson, LLD, Vol. II, “Of the Natural Rights of Individuals,” p.475. Philadelphia: Lorenzo Press (1804). https://hdl.handle.net/2027/mdp.39015011934414?urlappend=%3Bseq=485

- Lord Ellenborough’s Act (UK, 43 Geo. III, c.58) https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Lord_Ellenborough%27s_Act_1803, sourced from Pickering’s Statutes At Large (Cambridge University Press 1804 Ed)

- Akerly, Samuel, MD. (1808) The Medical Repository, Vol. 6. “Account of the Ergot or Spurred Rye,” pp.341-347. New York: Collins & Perkins. https://hdl.handle.net/2027/hvd.32044106439649?urlappend=%3Bseq=355

- Burns, John. (1809) Burns’s Obstetrical Works, “Of the Causes Giving Rise to Abortion,” p.34. New York: Collins and Perkins. https://hdl.handle.net/2027/osu.32436011220389?urlappend=%3Bseq=48

- Beck, John. (1817) An Inaugural Dissertation on Infanticide, pp.31. New York: J. Seymour. https://hdl.handle.net/2027/nnc2.ark:/13960/t0zp4v261?urlappend=%3Bseq=32

- Public Acts of 1821, §14. “Crimes and Punishments”, p.96. (Conn., 1821) https://hdl.handle.net/2027/mdp.35112105063657?urlappend=%3Bseq=114

- Rogers, Ammi. (1824) Memoirs of the Rev. Ammi Rogers. Hebron, Connecticut. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=osu.32435008061665&view=1up&seq=5&skin=2021

- Revised Statutes of Missouri, 1825, Vol I, Crimes and Misdemeanors, Ch. I, §12. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.hx2z91&view=1up&seq=7&skin=2021

- Criminal Code Act Div 5, §46; (Ill., 1827) https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=nyp.33433009071832&view=1up&seq=11&skin=2021

- von Baer, Karl Ernst. (1827) Ovi Mammalium et Hominis Genesi. Leipzig, Germany. https://www.google.com/books/edition/De_ovi_mammalium_et_hominis_genesi/cKZkAAAAcAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1

- von Baer, Karl Ernst. (1828) Über Entwickelungsgeschichte der Thiere. Beobachtung und Reflexion. Königsberg: Bei den Gebrüdern Bornträger. https://www.google.com/books/edition/Über_Entwickelungsgeschichte_der_Thiere/ev7OAAAAMAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=0

- Revised Statutes of New York, 1829, Title VI, Part IV, Chapter I, §21 (NY, 1828) https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.35112104871233

- Acts of Ohio, p.21, §2 (Ohio, 1834) https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=iau.31858017022355

- Laws of a General Nature, Ch. 47, §3 (Ind. 1835) https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc1.aa0002921237

- Penal Laws, Div. 14, §38. (Ga., 1833) https://hdl.handle.net/2027/mdp.35112105059978?urlappend=%3Bseq=853

- Revised Statutes, Ch. XLV, §§191-3 (Ark., 1838) https://hdl.handle.net/2027/nyp.33433009077029?urlappend=%3Bseq=336

- The Offences Against the Person Act, 4 Will.4 & 1 Vict. ch.85 p.496 (UK, 1837) https://books.google.com/books?id=KodKAAAAMAAJ&printsec=titlepage#v=onepage&q&f=false

- Commonwealth v. Demain et al., 1 Brightly 441 (Pa., 1846) https://hdl.handle.net/2027/chi.74255126?urlappend=%3Bseq=447

- Hodge, Hugh L. (1854) “On Criminal Abortion,” p.15. Philadelphia: TK and PG Collins, Printers. https://hdl.handle.net/2027/ien.35558005333212?urlappend=%3Bseq=19

- The Transactions of the American Medical Association v.XII i.0. (1859) “The Report of the Committee on Criminal Abortion,” pp.75-76. Philadelphia: Collins. https://ama.nmtvault.com/jsp/viewer.jsp?doc_id=ama_arch%2FAD200001%2F00000012

- Storer, Horatio Robinson, MD. (1860) On Criminal Abortion in America. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott & Co. Archived by Google at https://books.google.com/books/about/On_Criminal_Abortion_in_America.html?id=4kprAAAAMAAJ

- Storer, Horatio Robinson, MD. (1866) Why Not? A Book For Every Woman. Boston: Lee and Shepard. Archived at https://archive.org/details/whynotbookforeve00stor

- Dana, I.T., MD. (1866) Transactions of the Maine Medical Association, “Report on Production of Abortion,” pp.5-6. https://hdl.handle.net/2027/uc1.$b719573?urlappend=%3Bseq=50

- Le Prohon, Ed (1867) “Voluntary Abortion, or Fashionable Prostitution, with Some Remarks upon the Operation of Craniotomy.” Portland, Maine: Press of B. Thurston & Co. https://hdl.handle.net/2027/ien.35558000029823?urlappend=%3Bseq=19

- Journal of the Senate, appendix pp.233-235. “Additional Report from the Select Committee to Whom was Referred SB No. 285.” (Ohio, 1867) https://hdl.handle.net/2027/chi.78242783?urlappend=%3Bseq=965

- Gump, Daniel (2021) “Maps of Coverage,” Criminal Abortion Laws Across Before the Fourteenth Amendment, p.19.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!