A fetus is a child is a baby is a patient – 5 reasons to use the terms interchangeably

Today’s guest post is written by John Bockmann. You can also view his article as a Twitter thread here.

My older daughter, Emily, at 8 weeks’ gestation: “BABY.”

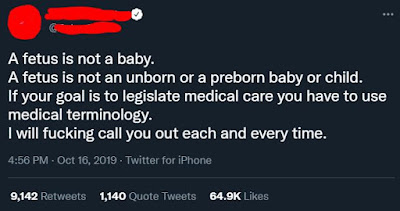

If you’ve ever debated abortion, you’ve probably noticed it’s nearly impossible to discuss the actual topic. Instead, the exchange rapidly devolves into accusations—often, that you’re using inaccurate terminology. This irate doctor’s tweet is a good example:

“A fetus is not a baby. A fetus is not an unborn or a preborn baby or child…”

But that’s incorrect: a fetus is a child is a baby is a patient, and the objection is strange if it’s meant to clarify medical terminology. But it’s not. It’s meant to rattle opponents and justify abortion, or at least obscure it. Let’s take a closer look.

1. First, crucially: abortion is killing. Since killing is not medical care, there is no requirement to use medical terminology and a lot of reasons to avoid it.

2. Second, nomenclature is an odd sticking point if the woman’s bodily autonomy is our only concern. What we call her womb-dweller—fetus, parasite, baby—should be irrelevant under this paradigm. Paradoxically, then, squabbling about terminology screams the fact that there is a baby, a morally relevant person, killed in every abortion.

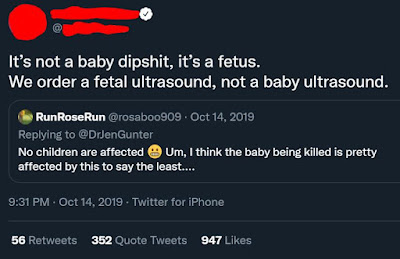

(Irate doctor strikes again)

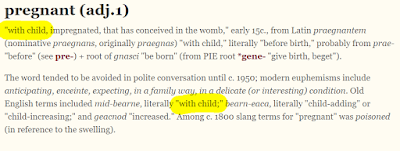

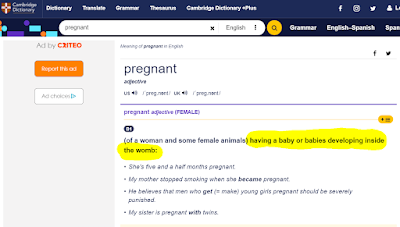

3. Third, the terms “maternal” and “maternal patient,” commonly used in reference to the pregnant woman, imply she is a mother, which implies she has an unborn child. “Pregnant” itself means “with child”—“having a baby or babies developing inside the womb.”

4. Fourth, the fetus is a patient in her own right. Sir Albert Liley, an atheist who performed the first successful fetal blood transfusion in 1963, conceived the medical science of fetology. In 1966, Journal of the American Medical Association noted his contribution, observing that “the fetus is a treatable patient.”

“My own practice makes it very clear,” he wrote in 1974, “that in modern obstetrics, we are caring for two individuals, mother and baby.”

Perhaps no two individuals illustrate Liley’s point more vividly than Julie Armas and her son, Samuel Armas.

The two underwent surgery to repair a lesion on Samuel’s back when he was a 21-week fetus. During surgery, he poked his left hand through an incision in his mother’s uterus and reflexively grabbed the surgeon’s finger. He took his first breath 15 weeks later.

Indeed, we are caring for two individuals. Maternal-fetal medicine is booming. Fetal surgery occurs at centers around the world. Williams’ Obstetrics 16th Edition said it well in 1980, and it’s even truer today: “Happily, we have entered an era in which the fetus can be rightfully considered and treated as our second patient.”

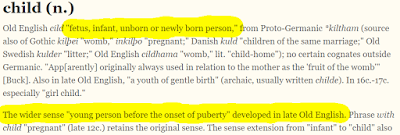

5. Finally, and obviously, the irate doctor is mistaken: “fetus,” “baby,” “child,” and even “patient” are standard terms for an unborn human being. In fact, “child” is the original, specific term for a prenatal human. The wider sense of “young person before the onset of puberty” came later.

Either sense is appropriate today: “Child: an unborn or recently born person,” says Merriam-Webster. The Oxford English Dictionary agrees.

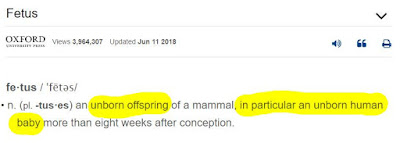

But even if we consent to only call the unborn human-thing a “fetus,” which simply means “offspring,” the definitions for those terms include “baby” and “child.” We’re back to our original position.

As we would expect, there are many, many articles in professional and consumer-oriented literature referring to the fetus as a baby or child. Here are some.

- Google Scholar has 22,800 results for “unborn baby” and 73,500 results for “unborn child.”

- Mayo Clinic’s “Pregnancy week by week” includes 10 mentions of baby. Babycenter’s version mentions baby 55 times.

- Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists’ 2010 study on fetal pain—one of two most frequently cited articles on the subject—calls the fetus a “baby” 27 times.

- The United Nations’ Convention on the Rights of the Child affirms that “the child, by reason of his physical and mental immaturity, needs special safeguards and care, including appropriate legal protection, before as well as after birth.”

- Cleveland Clinic’s summary of fetal development includes 83 mentions of baby: “At the moment of fertilization, your baby’s genetic make-up is complete, including its sex.”

- Judith Arcana, an abortion pioneer and advocate, calls the aborted fetus “a baby whose life is ended,” adding, “We—in the States—have dealt heavily, up to now, in euphemism…we have been unwilling to talk to women about what it means to abort a baby…I think this is a mistake tactically and strategically, and I think it’s wrong. And indeed, it has not worked…”

- Leroy Carhart, a physician who has performed abortions for many years, says: “I think that it is a baby. I use [the term] with patients.”

So the fetus is a child is a baby is a patient.

What, then, is behind the insistence that “A fetus is not a baby”? I think it’s an attempt to:

- protect oneself psychologically from the violent reality of abortion. Inserting a cold, clinical term for a familiar, sympathetic one creates an emotional buffer. As Jesse Jackson said in 1977, when he was pro-life: “They never talk about aborting a baby because that would imply something human. Rather they talk about aborting the fetus. Fetus sounds less than human and therefore can be justified.

- intimidate and stifle pro-lifers to keep them on the back foot. If pro-lifers don’t know the proper terminology or are misrepresenting it, then they’re not credible, their arguments may be dismissed, and the illusion of killing-to-heal can metastasize.

- lend medical legitimacy to killing–an approach with a long and sordid history.

Regardless of what we call a tiny prenatal human, though, I think few of our foes intellectually doubt the humanity of the fetus. Most of the resistance is instead emotional, and inaccessible to reason. The avoidance is psychologically protective for them, but it exacts a toll, and at least some of them yearn to be led out of their views.

But they won’t submit to someone they despise. The way forward, then, is to engage them on an emotional level first: cheerfully, wryly, calmly, curiously, firmly, perhaps with a wink, but always with kindness and confidence. Then, and only then, roll out facts like these. Proudly.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!