What Vietnam draftees and abortion-vulnerable women have in common

[Today’s guest post is published anonymously.]

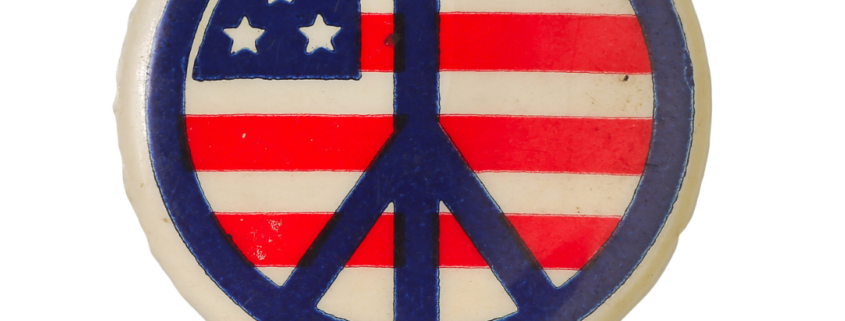

January 27, 1973. The Paris Accords formally bring an end to direct US involvement in the Vietnam War. The Vietnam war and the draft that it involved had been a major controversy for more than a decade. American society as a whole had formed a variety of opinions on the morality and practicality of the Vietnam War, but the generation of young men who were faced with the draft had to do more than form an opinion on a political issue- they had to decide how they personally felt about the prospect of participating in legally and socially authorized violence, and their response would shape the course of the rest of their lives.

January 22, 1973. The Supreme Court legalizes abortion nationwide in Roe v Wade. In the same week that young American men were released from the circumstances that forced them to either reject or rationalize institution-sponsored violence, American women were formally introduced to a new legal regime that presented violence against their unborn children as a legitimate choice and personal right.

Of course, this comparison between Vietnam-era draftees and the past several generations of women raised under Roe has limits, but we are overdue to take a step back from the typical historical analogies centered on human rights movements. Narratives centered on human rights are useful, but they have led each side of the abortion debate to take turns spiking the punch bowl of public discourse with self-righteousness to the point that anyone without a high tolerance for that intoxicating feeling hesitates to take more than a single taste.

The principal strength of this analogy is that it encourages a more nuanced understanding of women who consider or procure abortions. Like draftees shipped off to a war they did not choose against an enemy they did not understand, women in unexpected or unexpectedly difficult pregnancies are placed in a complex situation and handed a gun.

Some believe the propaganda- that the enemy is less than human, a threat to freedom and happiness, and so pull the trigger with anesthetized consciences. Others see through those lies, but still pull the trigger when they have reason to believe their own lives are in danger. Some shoot only because everyone around them is pressuring them to do so. Some would shoot if they were alone, but do not do so if they are surrounded by people they trust to keep them safe.

On the home front, some people bristle at any criticism of those involved in the conflict, naively believing that their beloved children would never kill unless it was absolutely justified. Others hear the stories of the worst violence done and denounce all those involved in the conflict as baby-killers.

Some who come home from the war eagerly take up sides in the political fight, either defending the necessity of their actions or denouncing the immorality or futility of their nation’s policies. But many more are too deeply affected by their experiences to know how to make sense of them. They are not certain if the decisions they made under pressure were the right ones. They are not confident that they can stand with one side or the other in defending or denouncing the war without making themselves hypocrites. Even if they do not wish they had made a different choice, they can still be haunted by their experience.

For as far back as I can remember, rhetoric surrounding abortion has centered on marshalling one side or the other toward the next electoral victory. As a result, half a century of American women have had their abortion-related experiences either ignored or weaponized, depending on how useful their stories are to people in power. This is understandable insofar as a human rights-centered narrative encourages us to think in stark moral terms: the side of good fights the side of evil in a never-ending battle to secure human rights.

But this leaves no room for those who have not processed the trauma of taking another human’s life, or who still regard their experience with ambivalence. They do not know how they feel about what they did, or what their decisions under duress say about what kind of person they are. Insisting that every abortion is equally justified gives them no more closure than denouncing every abortion as equally unjustifiable, just as telling returning soldiers that they are either heroic defenders of democracy or monstrous baby-killers does not do justice to their experiences.

The most obvious and necessary benefit of this Vietnam War paradigm is that it allows us to make more sense of the most common positions of ordinary people toward abortion. It invites us to consider that what activists on either side perceive as ignorance or apathy toward an issue of human rights might instead be deeply conflicted uncertainty based on either personal experiences or the experiences of those dear to them, and to make room for them in a debate that has been defined for 50 years by absolutist voices on either side.

The presumption of ignorance or apathy is not always unfounded, but pregnancy is so universally and unavoidably human that we should understand the impact of unexpected or unexpectedly difficult pregnancies in the decades since Roe to be even broader and more complex, though perhaps harder to track, than the impact of the military draft on one generation of young men. The broad center of American politics is not undecided on abortion: it is deeply- and understandably- conflicted in ways that the existing rhetoric, which is so frequently geared toward increasing political donations and voter turnout, does not address.

If you appreciate our work and would like to help, one of the most effective ways to do so is to become a monthly donor. You can also give a one time donation here or volunteer with us here.