Pro-Choice Thought Experiment: The Burning IVF Lab

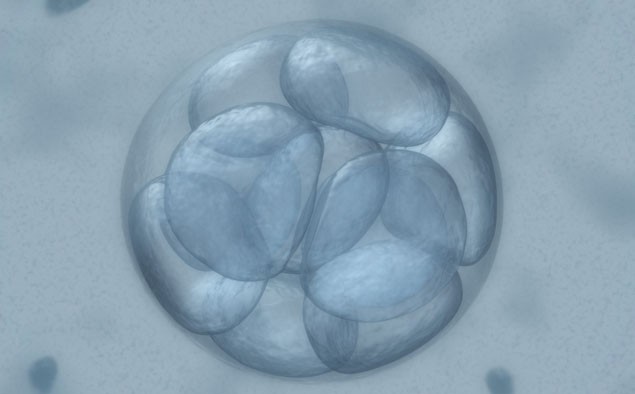

Dean Stretton imagines a case in which an emergency arises and a person is faced with the choice of rescuing ten frozen human embryos or five adult patients. Since virtually everyone would choose to save the adult patients rather than the embryos, this indicates that the patients have a higher moral status than the frozen human embryos. [1]

On the surface this seems to make sense. After all, the pro-life case is that from fertilization unborn human beings are morally equivalent to adults. You would think the ethical thing to do would be to rescue the greatest amount of humans possible, in this case the ten embryos. But if we would allow embryos to die in the fire by rescuing another human, how does that justify our intentionally killing them through abortion?

In Dean Stretton’s argument, the embryos in question were conceived through in vitro fertilization. That means we have no idea what’s going to happen to them. They may be implanted into a woman hoping to conceive (or several different women), or they may be used for research. This is tragic, but we simply don’t know the ultimate fate of these embryos. On top of that, even if they are scheduled for implantation, there’s no guarantee that all of them, or even any of them, will take. They may not implant. Therefore you would be morally justified in rescuing the adults, even over a greater number of human embryos.

[2] ibid., p. 139.

[3] Klusendorf, Scott, The Case for Life, (Crossway: Wheaton, Illinois, 2009), p. 42

[4] Robert P. George and Christopher Tollefsen, Embryo: A Defense of Human Life, Doubleday, 2008, p. 140.

[5] Ibid., pp.140-142.

Great post.

I explored this issue on Life TV a few months back…

Would you save 5 Embryos or a 2 year old child?:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wZ0acusUszM

Exactly. There's another pro-choice thought experiment I'm planning on responding to, but what most pro-choice thought experments boil down to is there might be different reasons one would not save an unborn child over a born person. But it doesn't follow from that that it's okay to intentionally kill them.

Funny as a prochoice advocate I read this and think this works. You're in a burning building (unplanned pregnancy) you need to make a choice about who you can save (the unborn or yourself or often for many women their family, existing children) from harm. You may choose to save the unborn child, you might choose to save the existing family, or yourself.

I know, it's not what you intended. We make choices all the time in life, perhaps not a urgently needed as in a burning building about how to allocate resources, who to "save"

Sure, if the only time the mother chooses to have an abortion is when the mother will die. Other that that, though, what else does it prove?

I understand that life of the mother may be the only justifiable reason in your mind for a woman to seek an abortion. But the loss of other things can be drivers too. And in the case of the experiment I see "burning building" could be any number of valid reasons to not want to carry a pregnancy to term

It's just perspective. This will probably make perfect sense to someone prolife. To someone on the other side it's just as easy to see that sometimes we make choices about what/who we save

Regardless of whether the point of the article was right or wrong, this argument here is the most retarded and unreal line of BS I've ever heard, since it's been US leaders that have caused the most instability, destroyed millions of peoples lives and caused most recent civil wars. Most US presidents have been war criminals, including the current one and the last 6 prior. "The regular person and the President have equal rights to live. However, unlike killing a regular person, killing the President may also generate global instability, upset millions of people, and perhaps even prompt massive retaliation or world war. These factors make the assassination of any world leader more grievously wrong than killing a private citizen…"

You've missed the entire point of the thought experiment. The point is, allegedly, that since pro-life people would rather save an adult rather than ten embryos, they obviously don't *really* consider the unborn to have the same moral status. The thought experiment fails miserably for the reasons I laid out.

I see your point, but choosing to save a toddler and leave an embryo to die because you can only save one, is not the same as actively killing the embryo/fetus, which is what happens in an abortion. Plus, you could easily apply your argument to a newborn. If a woman has a toddler already and then gives birth to a newborn, she can't justify killing the newborn on the grounds that she's already struggling financially, or that she's got more time and money invested in the toddler, or that people have gotten to know the toddler and will therefore miss him more. The latter two reasons may impact her decision of whom to save from the burning building, but they certainly don't justify her deliberately killing her newborn.

I understand your persective.

For a woman facing an unplanned and unwanted pregnancy, or needing to terminate for a medical reason she's concerned with saving herself from the burning building that is her situation

The idea works for people who are already prolife because you approach it from the idea that a frozen embroy is equal to a newborn.

Someone prochoice doesn't see them as equivilent so presenting the idea of killing a newborn because you're financially struggling is just too extreme and makes them stop listening to the prolife arguments because the gap is too great to bridge

If prolife approached these things more from a practical aspect I think they would be more successful

Do people say that to you?

Interesting

Here's my response:

You are at an IVF clinic when a fire breaks out and you must choose between saving a single frozen embryo or every employee, volunteer and donor of NOW, NARAL, ACLU & Planned Parenthood who are holding a

baby-killing conference in a connected conference center. Which would you choose?

http://www.personhoodusa.com/imagine-the-ivf-clinic-is-on-fire/#.UlcF3RAudmU

Is that you Clayton Waagner? Does this mean they've got internet access at Lewisburg now?

Say what to me? That's the point of the thought experiment. It's even outlined in the Dean Stretton quote.

I've read your comment and I plan to respond, as soon as I have more time.

Great. On a different subject, have you read J. David Velleman's "Against the Right to Die"? Its about physician assisted suicide, not abortion, but I think that its useful in the abortion debate/ discussion as well. His point, or at least one of his points, is that having some choices available might actually make you less autonomous. http://www.academia.edu/2048245/Against_the_Right_to_Die

Sorry for the delayed response.

Aborting a pre-born child because they're unwanted or inconvenient isn't like saving herself from the burning lab, any more than killing her infant would be. Clearly killing her unwanted/inconvenient infant to "save herself" isn't accapteble. Aborting because her life is legitimately in danger, however, could be compared to running out of the lab. (Although there are complexities to this situation that are, in part, explored in a blog post from a couple days ago.)

If you want to say that certain circumstances warrant the killing of the pre-born child but not the born one, you have to have a good justification for why pre-born humans don't merit human rights. I can see what you're saying about claiming that an embryo is a human being seeming "too extreme," but honestly, that's the whole point. With what other approach can I claim that it's unjust to kill an embryo if the embryo isn't a human being?

People, understandably, simply have a hard time relating to and empathizing with very hard humans, and that makes it hard for them to see abortion as discriminatory. But that's always the case: if someone is different or hard to relate to, we dismiss their humanity and justify their suffering. In the past it sounded extreme to say that women were full human beings that warranted the same rights as men. But obviously they are.

Er, "very young humans…." My typing got ahead of my brain.

I think thought experiments/analogies do work at times, but you have to be careful with them. They can be misleading, and can lead you to the wrong conclusion. The problem is that thought experiments have to be like the situation in morally relevant ways. If it's not, then the thought experiment doesn't work. This thought experiment is just meant to argue that pro-life people don't really consider the unborn to have as much value as born human beings. And it ultimately fails, for the reasons I outlined.

So I think it is a non-sequitur (since even if the thought experiment succeeds, it doesn't justify intentionally killing the unborn just because we might let them die to rescue an older human being), though not because of the "life of the mother" exception.

And you are correct. We don't value the unborn as *more valuable* than the pregnant woman, they are *equally valuable*. It is a question of interests, and the hierarchy of rights. The right to life is the most fundamental of all human rights. It makes no sense to claim I have a right to free speech if I don't even have a right to live. I have actually posted an essay on this blog talking about rights that you might be interested in reading. Essentially, the argument is that the unborn child's right to life trumps the right to bodily autonomy, because it's a more fundamental right (and in the vast majority of cases, the child exists because of a voluntary action by the woman). But the argument can also be made that an abortion is a more egregious harm to the unborn than to the woman, because not only are you violating their right to life, you're also violating their own righ to bodily autonomy. So that's two violations of imortant rights (the unborn) versus one (the pregnant woman), and arguably it's not even a violation of the woman's bodily autonomy since by engaging in sex she tacitly consents to let the unborn use her body.

So I don't think your thought experiment succeeds. In the vast majority of cases the woman willingly engages in an act that produces a child and places that child in a naturally needy condition. So it doesn't account for the responsibility aspect. But also, I think your modified thought experiment more accurately accounts for the difference between the rights, and I might need to mull it over a little bit. I do think that your modified thought experiment makes a better case than the original thought experiment does. The only thing I might say is that a doctor should be able to do both, save the embryos first because it's immediate, then treat the people who are suffering from depression. Unless they're all suicidal, but then you're back to square one, debating which ones you should save.

Well, for what its worth, Velleman's piece was IMO the best piece of philosophy by a living philosopher I read as an undergrad and IMO is much better philosophy, unfortunately, than most (perhaps all) of the contemporary philosophy regarding abortion. So even though it undermines the pro-choice position (to a degree) I thought I'd pass since I recommend it to everyone who has an interest in ethics in general, and it is pretty much on point here.

Other than the tacit Lockean tacit consent argument, which I don't think works for Locke either, I think I agree with that. As I've said before, although we disagree here (of course), trying to ground ethical/legal responsibility to give birth in the free choice to have sex (especially sex using birth control) is problematic because there is not a sufficiently analogous situation in which attach the same sort of responsibility/burden to one of the "responsible" actors (which is why, among other reasons, I think that, ultimately, the argument by analogy line of reasoning isn't very persuasive for either the pro-choice or pro-life arguer).

I don't expect you to understand how a woman who feels that a pregnancy could be equal to being in a burning building. Like pregnancies, it's a very individual thing, the circumstances of a life, what that person is facing, how multiple factors come together and she decides to either carry to term or abort.

In your mind, the unborn baby, at any stage is the same as an infant.

In many people's mind, it is not.

And even in the minds of many women who seek and go through with an abortion, often the reasons aren't so much that the child is inconvenient or unwanted, they could very much want a baby but just not see how they can manage it, or there are issues with the health of mother or child, or any number of reasons, and they decide, overall that now is not the right time for that pregnancy.

Again, it's just that the fundamental divide is that you see the pregnancy from conception as a infant, and we (they) do not

That said, should you then be able to impose your values on the woman who doesn't believe as you do and if so, what do you think should be done to assist her with the difficulties she will face, and how do you suggest enforcing a ban?

I am generally sypathetic with much of what you say, especially regarding what this bioethical dilemma does not establish. But we need to be more circumspect before suggesting that it has no normative impetus whatsoever.

To wit:

http://www.scribd.com/doc/196706115/Bioethical-Dilemma-of-Saving-Embryos-From-Burning-Building