Civil disobedience, the FACE Act, and the prisoner’s dilemma

You may already be aware of the federal prosecution of several members of Progressive Anti-Abortion Uprising (PAAU) under the Freedom of Access to Clinic Entrances (FACE) Act and the trial that began in Washington D.C. this month.

I’m a long-time Secular Pro-Life supporter who values well thought out exchanges backed by evidence over more aggressive tactics. I’m not always sure what I think about PAAU’s methods and the acts that lead to these charges. This trial has me thinking more about it, so when PAAU hosted this webinar, I tuned in to hear their side of the story and learn more about the action that led to their indictment: Rescue.

During the webinar, PAAU Director of Community Organizing Kristin Turner suggested the repeal of the FACE Act should be the next major goal of the pro-life movement. The following are my thoughts on the FACE Act based on the information and ideas they shared in their webinar, and particularly based on Turner’s suggestion.

Civil Disobedience: Finding the Compromise

As PAAU explains it, Rescue is “the act of entering a clinic to put your body nonviolently between the killer and the baby.” It is a way to stop or delay abortions. PAAU and others consider this a form of civil disobedience, drawing attention to an issue (abortion, in this case) while putting a temporary hold on a perceived injustice.

Despite this being a pro-life blog, pretend, for a moment, that we are not talking about abortion. Let’s talk more generally about civil disobedience and the roles of government towards members of the public who engage in civil disobedience.

Civil disobedience is when people intentionally break the law in order to make a statement to that government and society as a whole, of a need for change in the way society conducts itself. The government, in theory, should be able to address the various concerns of a society in a democratic system. However we all recognize that, for both practical and often political reasons, not every topic gets brought up or thoroughly investigated. Civil disobedience is the escape valve to bring attention to an issue that for reasons accidental or instrumental, remains obscured, propagandized, or otherwise ignored.

Abortion is hardly the only topic that has drawn acts of civil disobedience. Mountaintop removal protests—where activists chain themselves to trees, homes, and even cars to stop the machines that would otherwise tear apart the mountains they live among—are literally the last line of defense people have had against coal mining companies with seemingly limitless funds to buy laws from politicians. Animal rights activists often invade farms to rescue animals from mistreatment. Keystone XL would have likely continued construction had it not been for numerous acts of civil disobedience.

Civil disobedience is open and democratic, available to almost anyone in society who may or may not have political power in other forms: from prisoners to children to documented non-citizens. It offers a simple but powerful response for a group perceiving gross injustice to be able to stand against forces with vastly more power, money, and resources. In a democratic society, we want civil disobedience to remain an option.

But that doesn’t mean civil disobedience is always the best option. It is not an impact-neutral action to society. When civil disobedience, by intent or by accident, interferes with the systems the public relies upon, individuals may suffer. This could mean higher electricity prices resulting from protests against coal mining, lost wages for loggers denied a timber harvest, or—as the climate advocacy group Stop Oil found out earlier this year when protesting an overreliance on fossil fuel dependent transport—delay of emergency medical services for those traveling via highway.

In the face of those impacts, government has an incentive to maintain stability. Where civil disobedience is responding to minor grievances, or where problems can be better addressed in other venues (such as through law or education), the benefits of civil disobedience can be overshadowed by the costs of these societal disruptions.

The compromise is built into our system. Civil disobedience, which is lawbreaking, often meets with arrests and charges. Activists must have “skin in the game.” When people have to sacrifice, they are less likely to use civil disobedience as a means of communicating frivolous concerns or concerns that can be addressed in other venues. Government does have an incentive to make civil disobedience an undesirable act in and of itself.

In sum, even if I celebrate any children that are alive today because of PAAU’s actions at the Washington D.C. clinic a couple years ago, the idea that people should have to face some kind of consequence for intentionally breaking the law isn’t objectionable. It is a demonstration that PAAU has “skin in the game” that they commit these actions despite the existing disincentives of normal laws. The question at hand is: has civil disobedience been made so costly as to remove it as possible option for anyone, nullifying its beneficial effects to the democratic process?

Proportionate Government Response to Civil Disobedience

Government has a clear tool to disincentivize frivolous civil disobedience, via application of the very laws being broken. Usually these infractions are comparatively minor, such as trespassing, or perhaps theft, and there are thousands of cases of such infractions that aren’t related to civil disobedience which we can use to compare and to ensure the law is being applied fairly. As with any government policy in a democratic society, consistency is key. Treating similar actions similarly under the law, regardless of what they stand for, is how institutions maintain legitimacy and trust. If the public views the law as being unequally applied, they lose faith in these institutions.

In many examples of civil disobedience, most recognize the need for this legitimacy. Animal rights acts of civil disobedience get charged for trespassing (if they get charged at all). Alternatively, when government response to civil disobedience seem designed specifically to favor special interests, and go above and beyond what the law requires for similar infractions outside of civil disobedience, the response typically fails. Protests against Keystone XL resulted in massive arrests and charges against protesters. Even though the charges were not specific to climate protesters against a fossil fuel company, prosecutors went out of their way to bring harsh charges to protesters, going so far as to charge a couple of people with “Aiding attempted suicide” by hiding in a pipe as a way to stop construction. As one defense attorney noted, “To put it charitably, it’s a very creative use of this law.” It is likely the extreme prosecutorial overreach is a reason none of these charges stuck, and nobody has been convicted. By forcing prosecutors to work within the normal scope of the law, response to civil disobedience cannot be frivolous or designed to benefit special interests.

Additionally, politicians friendly to Keystone XL’s company Enbridge introduced several bills in Minnesota with language specifically to prevent pipeline protests; thankfully, these failed. In other states where laws have been stretched to accommodate fossil fuel exploitation and transport as “critical infrastructure,” allies and watchdogs alike have rightfully decried such victories for entrenched and moneyed interests at the cost of the voices of the people. There are no federal regulations that have passed marking pipelines or the targets of other environmental protests as worthy of special protections against civil disobedience.

So, taking another look at civil disobedience regarding abortion, it’s interesting that there is a very specific act, the FACE Act, designed to defend only “reproductive services” by creating much harsher consequences for civil disobedience beyond normal laws regarding trespassing and property damage. This incongruence hits harder with Lauren Handy’s observation of her trial:

Because abortion is no longer a federal right they’re not even talking about this anymore as abortion is healthcare, they’re talking about this as commerce. That it’s interrupting commerce.

Lauren Handy

The FACE Act is designed to protect a specific type of commerce against civil disobedience.

In their webinar, PAAU also goes on to suggest that the FACE Act is even more inconsistent in its application within the realm of “reproductive services” given the wave of pregnancy resource center (PRC) vandalism following the fall of Roe. They suggest that while this vandalism clearly falls within the language of FACE, none of the vandals have been charged under it. However, in the interest of fairness, at least a few have been charged.

So the FACE Act seems to exist on shaky grounds, albeit not as shaky as PAAU may think. Still, the special attention to the protection of any one specific type of commerce against civil disobedience should warrant concern from every American, even if you are pro-choice. If FACE stands, and the members of PAAU are ultimately convicted, it sets precedent for any other type of commerce, including fossil fuel companies, to invest in politicians that will give them similar protection laws. There will be no mechanism in the courts to indicate why such a law shouldn’t pass.

Visibility and the Prisoner’s Dilemma

The Prisoner’s Dilemma is a thought experiment in game theory used to help model decision making processes for people on whether or not to cooperate with one another. The model goes as such:

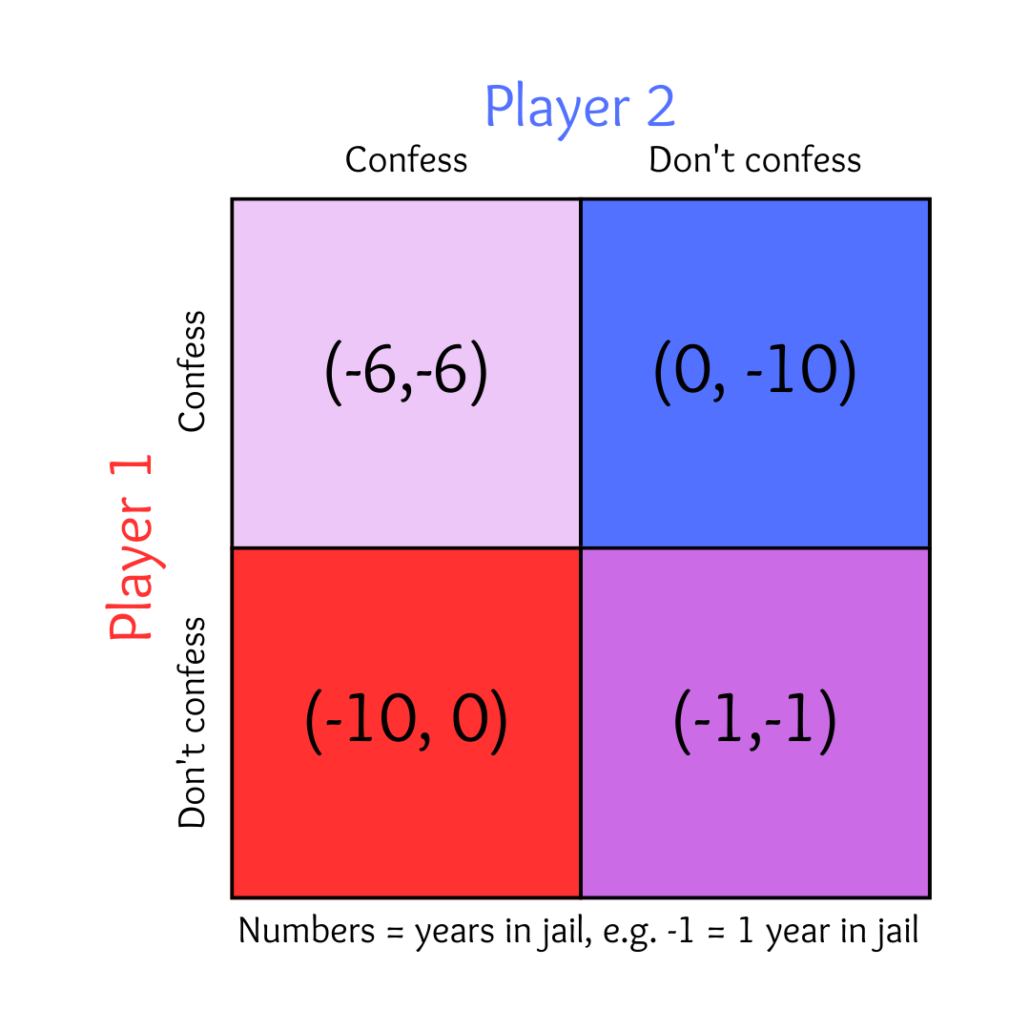

Player 1 and Player 2 are convicted of a minor crime, but are also guilty of a much greater crime for which police do not have sufficient evidence for a conviction. Each player is isolated and offered a deal if they turn on one another. Thus players have the following options:

- The two can cooperate, keeping the secret safe, and each of them will be punished only for the minor crime (-1 in the image below).

- They can take a plea deal, revealing the major crime and testifying against the other.

- If (for example) Player 1 rats out Player 2, Player 1 gets no jail time and Player 2 gets 10 years (-10 in the image below).

- If, however, both players confess, they will both get a hefty sentence (-6 in the image below) that they could have avoided if they had both been silent.

The essence of the game is that when the two players can’t communicate to coordinate their response, each must make decisions isolated to their self-interest. Regardless of the other person’s action, the incentive will always be to confess. If they confess and their partner does not, they get off with 0 years in prison. However, it is also true that if their partner confesses, it is better they confess, otherwise they will get 10 years in prison, versus the 6. In this way, individual self-interest results in overall worse outcomes.

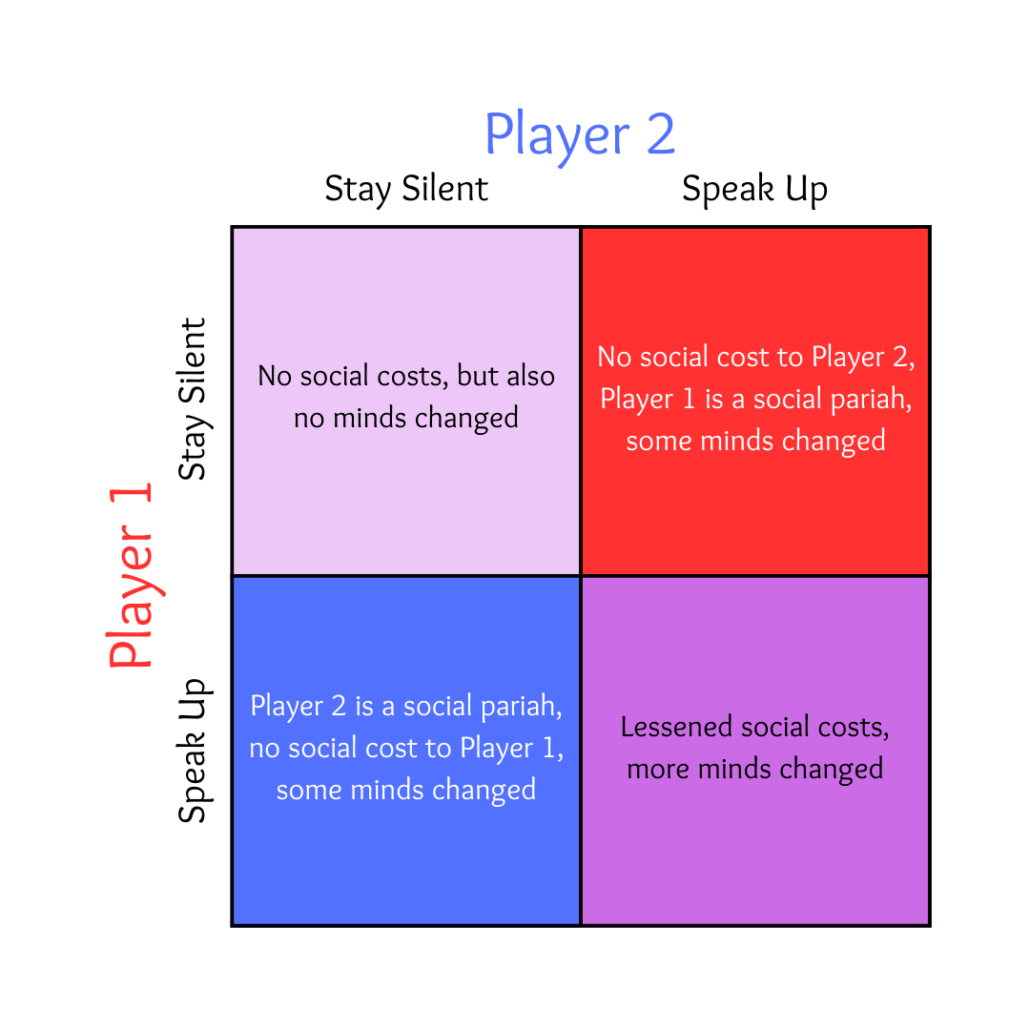

PAAU goes on to outline a very real phenomenon in the pro-life world, especially for those of us in blue states and who are more on the blue side of the political spectrum: the FACE Act has decreased pro-life visibility and left this substantial minority position very isolated. Kristin Turner accurately describes that in places like her home state of California, pro-life laws are nowhere to be seen and will not be feasible for the foreseeable future. And these are places where there is a very real social cost to espousing pro-life views. This acts as sort of a reverse prisoner’s dilemma.

In this scenario, Player 1 and Player 2 are people with pro-life beliefs who want to see an end to elective abortion, but they are isolated. They each suspect they are the only one out there with these beliefs. In our oversimplified prisoner’s dilemma model, it might look like this:

Again, when people can’t communicate to coordinate their response, more of them will make decisions based on which option maximizes their interests. In this case, interests include impact they can make on the abortion debate and their ability to minimize negative social repercussions. But unlike in the original prisoner’s dilemma, where the incentive is to speak up, here the incentive is to stay silent.

But silence is not optimal for long-term pro-life goals. If they could find each other, communicate, and agree to take a stand together, they could change some minds while benefiting from the social capital of strength in numbers. Social costs may also be mitigated by new social connections.

However, in many areas of the country where pro-choice is considered standard, outing oneself as pro-life is only going to happen where people already trust they will have the community to withstand backlash. Trust takes time to build, and cannot be easily acquired with strangers, so social ostracization naturally limits coalition building.

The nature of rescue and other visible pro-life activities, helps to break down this communication block paradigm by making it clear that these individuals are not alone. It decreases the impacts of social backlash through strength in numbers, making the modest gains in minds changed more worth the effort. Something like the FACE Act necessarily counteracts these effects. In addition to social costs, FACE can potentially add legal and financial costs, which further increase the risks in speaking up and further isolate like minds.

Anecdotally, having lived in blue states as a liberal for almost all my life, it seems to me this chilling effect has played out. There was little-to-no social cost to being pro-life in the 90’s and even the early 00’s. Disagreements, plenty. But being pro-life didn’t cost me friends like it does now. Before this trial, I hadn’t considered that the death of movements like Rescue and the impacts the FACE Act may have played a role in this transformation of our national dialogue, but the timing is certainly suspiciously similar.

Wrap-up: Cost Benefit Analysis of Priorities

If the goal should be to maintain the option of civil disobedience, which is necessary in a healthy democracy, the FACE Act seems to exist on shaky ground. Further, it has a chilling effect on the visibility of the pro-life movement and the ability to make cultural headway in places where the law is not going to be on the side of fetal rights any time in the near future. Repealing FACE is a worthy goal of the pro-life movement.

Should it be the pro-life movement’s primary goal? Every movement is limited in people, funding, and effort that can be made to advance a specific goal. And it is here where PAAU’s arguments get muddier. Rescue is not the only way to accomplish visibility. I am not even sure if it is the best way to accomplish visibility. And while even non-rescue activities may be chilled by the FACE Act, the data either way seems slim.

And how about the babies themselves? Is rescue directly saving lives? PAAU provides anecdotal evidence that the Let Them Live hotline is receiving calls after rescues, but there aren’t solid numbers. It’s unclear whether they can trace calls back to a specific rescue and whether those who call end up carrying their pregnancies. At the time of writing this post, we don’t have specific examples of women coming forward with their stories of how rescue positively impacted them. None of this is to say there aren’t such women, but in an attempt to assess which goals should be the primary focus of the pro-life movement, it would be helpful to have quantifiable data.

Meanwhile there are other potential priorities for PLM. Should the movement focus on improved mobilization state-by-state? Should it be pushing for a federal 15 week ban? A federal heartbeat ban? An expanded interpretation of the 14th Amendment? The repeal of the FACE Act is a worthy goal, but in a reality of finite resources, how that goal fits in with all else depends on the costs of achieving it and the potential benefits once its achieved. For me, I’d say it’s unclear.