Book Review: “Random Family” Teaches Valuable Lessons About Pregnancy and Poverty

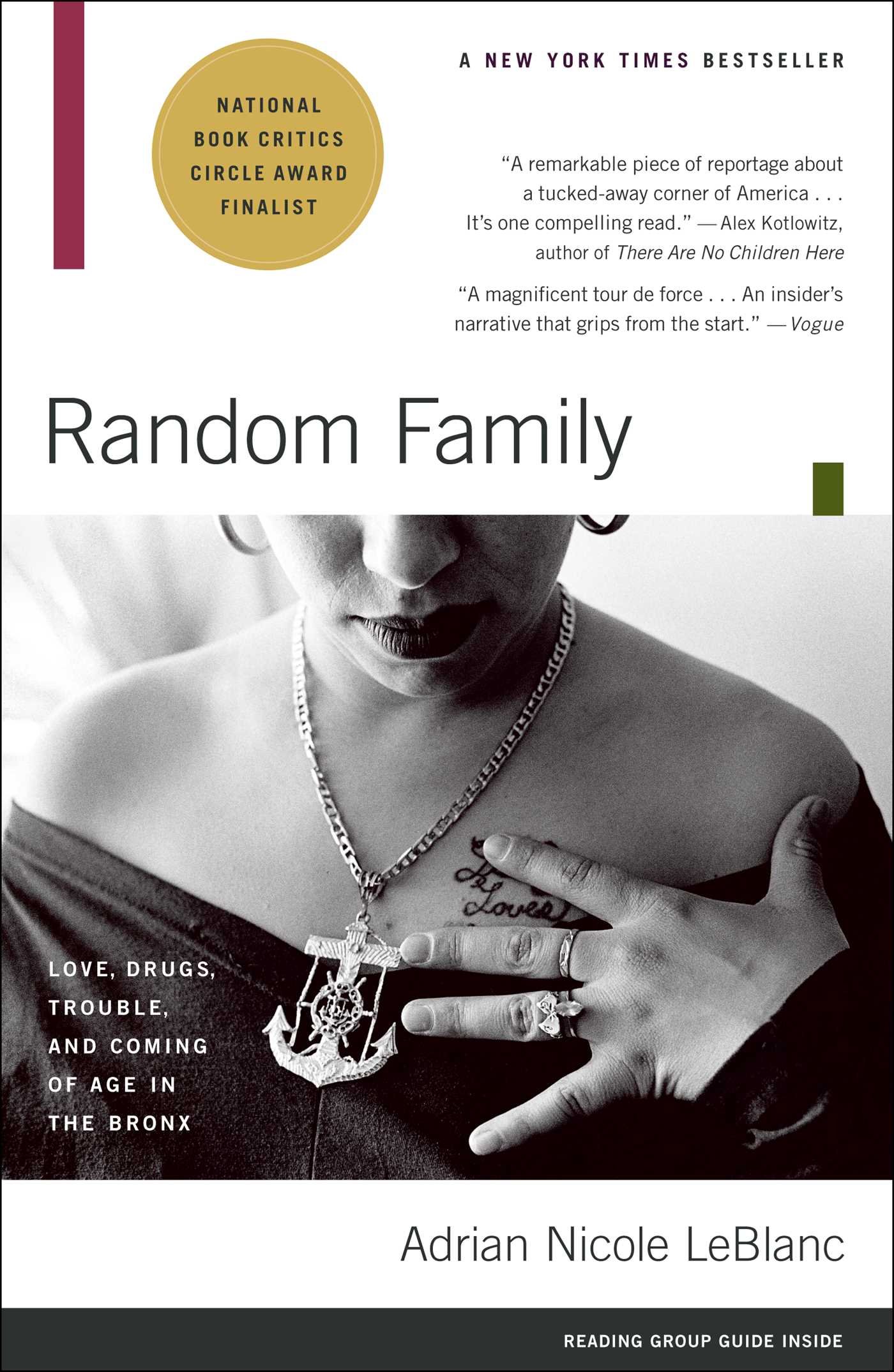

I recently read Adrian Nicole LeBlanc’s 2003 masterpiece Random Family: Love, Drugs, Trouble, and Coming of Age in the Bronx. LeBlanc spent over a decade chronicling the lives of people in some of New York’s poorest neighborhoods at the height of the crack epidemic. As so often happens when I read to try to take a break from pro-life advocacy, it turned out that Random Family has a lot to say about abortion.

The subculture Random Family explores has a reputation for treating human life as cheap. In some ways, that checks out: drug cartels run the streets, boys join violent gangs, and domestic and sexual abuse are rampant. And yet…

You could hate a rival all you wanted to, but pregnancy merited respect. There were girls so hard that they paid no mind to a belly, but Coco wasn’t one of them. After all, the unborn baby was innocent.

Typical pro-choice euphemisms are completely absent from the protagonists’ language. Teen and unplanned pregnancies are common, but abortion is rarely on the table. When it is, everyone recognizes the reality that abortion kills a baby.

Coco considers abortion twice. First, she becomes pregnant while her true love, Cesar, is incarcerated, and Cesar breaks up with her:

Coco reasoned that since the baby made her lose Cesar, the loss of the baby might bring him back. She made an appointment for an abortion. She went to the clinic but forgot her Medicaid card. She rescheduled and missed the second appointment. She finally went for a third, but she’d lost heart. Coco’s sister, Iris, remembered Coco punching herself in the stomach and throwing herself against the wall. “She did everything to try and get rid of that baby,” Iris said. But the baby survived all of it, so Coco reckoned it was fate.

That baby is Nikki, Coco’s second daughter. Two more daughters follow. Coco then attempts to obtain birth control, prompting the sole appearance of Planned Parenthood in the narrative. Planned Parenthood does not come off well:

Coco kept her appointment at Planned Parenthood and decided on the Depo-Provera shot, but she didn’t react well to it. She bled heavily for a solid week; when she reported to Planned Parenthood again, she was instructed to continue taking Motrin. Coco asked if she could get her tubes tied and was told she had to make several appointments, including one for an hour of counseling. Between her chronic problems with Frankie and with Pearl, she never made it back.

Yes, you read that right: Planned Parenthood, which regularly battles against basic informed consent laws for abortion, required a mother of four to have an hour-long counseling session and jump through hoops before she could get a tubal ligation! Perhaps they were hoping to have her back as an abortion customer. Little surprise that Coco becomes pregnant with a fifth child. She feels overwhelmed and ambivalent — but her oldest daughter, eight-year-old Mercedes, intervenes:

Coco considered getting an abortion, but then she thought about what people would think of her for murdering an unborn child. One night, she polled her daughters on the way to the dollar store. “Mommy might take out the baby. I went through the same thing with the four of ya’aw, but I thought I could do it, and there’s so much I want to do for you — you know how Mommy wants to go to Great Escapes? And I swear, I’ll get you there this summer if I have to rent the damn van myself. But I can’t do this.”

“Mommy, that ain’t right,” Mercedes said.

“I know, Mercy, but Mommy can’t do it. You see the problems I got with Frankie now?”

“But Mommy, it ain’t right,” Mercedes said again.

“We’ll help you, Mommy,” Nikki said. “We can make the bottle.”

With her daughters’ encouragement, Coco chooses life for their little brother La-Monté.

Another close call occurs when Cesar’s sister, Jessica, is in prison and begins a sexual relationship with a guard named Torres:

The prison authorities had given Jessica a pregnancy test that August, which was negative; but by October, the blood test came back positive. Jessica asked for an abortion but said the prison refused to give her one unless she paid for it. She didn’t have the money. She called her former pro-bono attorney, but by the time he had intervened and the abortion was scheduled, Jessica had spoken with Torres and changed her mind.

The officials’ refusal to pay for an abortion with taxpayer funds saved two lives; Jessica was carrying twins. LeBlanc writes:

Babies were about hoping and growing, not just surviving. They pulled you into the future, even if you were literally imprisoned by your past. Any belly — inside or outside of prison — required at least the perfunctory gestures of optimism. . . . Ida was the cook of the bunch, and she made it her business to keep Jessica full of food. Ida had been pregnant when she was arrested and still regretted her abortion; Jessica’s pregnancy offered her a second chance to do right.

Random Family is anecdotal and several years old, but more recent data agree: low-income, marginalized communities tend to hold anti-abortion values. A 2019 Gallup poll found that a strong majority of Americans with household incomes under $40,000 took pro-life positions, saying that abortion should be illegal in all (30%) or most (40%) circumstances. Among those with incomes over $100,000, the pro-choice position prevails. The abortion industry cynically casts itself as the voice of low-income people, but that’s a lie. If elites actually listened to the poor, they would learn that abortion is not an acceptable solution to the problems of poverty.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!